While making ALMOST THERE was a life-altering experience for co-director Dan Rybicky, our team’s first encounter with the Chicago based filmmaker could very well be described with the same term. Seldom have I seen a similar expression of joy and gratitude as when first meeting and shaking hands with Dan at this year’s Sheffield Doc/Fest. Hence, I am happy that we have the opportunity to feature ALMOST THERE, a documentary brought to us by a brilliant, congenial team of filmmakers who try to brighten the future of an amazing artist buried in the past. ALMOST THERE might be Dan’s first full-length feature but he is no stranger to the film industry. With an MFA from New York’s Tisch School of Arts under his belt, he got involved in various production capacities for filmmakers like Martin Scorsese, John Sayles and John Leguizamo. In his current position as Associate Professor in Cinema Art + Science at Columbia College Chicago he is at least as cherished by his students as he was by me throughout the interview, so let’s have a closer look at the first of the two creative minds behind our December doc.

What is it that draws you to documentary film?

I love how passionate, purposeful and humane documentary films and filmmakers are, and I’m challenged in a wonderful way by the inherent tensions and complexities contained within John Grierson’s early definition of documentary as “the creative treatment of actuality.” Best of all, I’m grateful for the discoveries I’ve made and lessons I’ve learned during the process of shining a literal and metaphorical light on the always fascinating, unpredictable, and inspiring lives of the real people I’ve met – and those I look forward to meeting soon.

What is your history? Is there a red thread that has followed you throughout your career as a documentary filmmaker and in other pursuits?

For better or worse, I’m a person who has always picked the scab and scratched the itch, even when I was told not to. As a kid, my family called me “the shit disturber” because I spoke out about the lies and injustices I saw to those close to me who preferred, and even demanded, silence. I’m sure I was really annoying (and probably still am), but this early quest for truth (which has evolved into more of a meditation on what truth is and isn’t) – combined with my endless curiosity about people and why and how their stories are told – first led me to pursuing a career as a playwright and screenwriter. And while I do still enjoy putting my words into other people’s mouths, I’ve become increasingly more interested in listening to non-actors speak their own words and seeing how the narrative structures and character arcs I’ve employed in my fiction apply – or don’t – to the complicated lives and surprising stories of real people. Ultimately, it is my deep love for these real (and really great) characters – especially those who are at a turning point in their lives and deeply desire something – that has made me become a documentary filmmaker.

So, you came across Peter Anton at a Pierogi Festival – probably one of the most fun stories a filmmaker can tell about how they found inspiration for a new project. What sparked your interest? At what point did you decide to start working on Almost There?

It’s true that my friend and co-director Aaron Wickenden and I first met Peter Anton during the summer of 2006 at Pierogi Fest in Northwest Indiana, having initially gone there because the festival was trying to get into the Guinness Book of World Records by unveiling “The World’s Largest Pierogi.” We brought our cameras with us because we thought that buttery mountain of dough would be a sight to behold. Little did we know we would encounter someone who would change the course of our lives for the next decade.

Peter was sitting at a rickety table off of the main festival path dressed like a disheveled dandy persuading passersby to let him draw their portraits. We were charmed by his corny jokes and mesmerized by how much the kids he was drawing loved him. And then from under his table, Peter pulled out one of his twelve gigantic and totally handmade scrapbooks. It vibrated with color, glitter and text, and we were immediately drawn in.

We wrote letters back and forth for two years before finally visiting Peter at his house in 2008 so he could show us more of his art. When we got there, we were deeply saddened yet intrigued to learn that Peter was a hoarder living in extreme squalor, surrounded by artistic gems buried in rubble and mold. We were excited to discover this body of artwork but majorly concerned for Peter’s well being. What shocked us the most was how determined Peter was to stay living in such life-threatening conditions. After offering Peter information about social service organizations that could help him secure better housing, we were finally forced to accept Peter’s wishes. But because we remained interested in this tension between the past and present that exists in Peter’s art and life, we began documenting him, his house, and his art before everything was damaged beyond recognition.

Almost There is a very personal film, focusing not only on Peter but also on you as you become a subject of the documentary and share your personal history. When did you realize that you would become a part of the story, and what was that experience like for you?

Aaron and I did not begin this film wanting or expecting to become supporting characters in it, but while reviewing our footage, we realized some of the most dramatic exchanges that brought the deepest conflicts of Peter’s life and story immediately to the surface were between him and us. This is not so surprising in retrospect, considering Peter lived in almost total isolation and we were two of the only people he would see or talk to for weeks at a time.

But only during our fourth year of our collaboration was I able to more deeply explore my own motivation for telling Peter’s story when, soon after the art exhibition in Chicago we had helped Peter set up, a journalist discovered a disturbing secret from Peter’s past – something he had kept from us. My friends saw how upset Aaron and I were about it and started to ask me why I was still documenting this man’s life now that he’d lied to us. Why did I feel the need to continue helping Peter so much even though he actively refused to help himself?

During a visit to my hometown, I began to look more closely at the parallels between Peter’s story and the story of my family and quickly realized how much my desire to help Peter in the present was related to my not being able to help my own mentally ill brother in the past – a brother who, like Peter years ago, was an artist still living in the house he grew up in with his (and my) mother.

I’ve always been wary of the ‘God-eye’ in documentary anyway and often wish more directors revealed on screen the ethically complicated and hard-to-define relationships that have developed between them and their subjects over the course of filming. Although this is usually the stuff they edit out, these “behind-the-scenes” negotiations and power dynamics contain stories I find as interesting, if not more interesting, than the ones the directors have chosen to tell. Based on this, and based on my determination to hold myself up to the same scrutiny I give to a subject, Aaron and I decided that developing my character and showing my motivations would add an additional layer of depth and context to our story and pull the veil back even further on the process of documentary making itself.

Comparing his situation to van Gogh’s Peter says: “Only the art matters, not the mess.” Having been a regular at Peter’s, what is your opinion?

As Victor E. Frankel wrote in one of my favorite books Man’s Search for Meaning, “Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how’.” Peter definitely confirmed my belief in the truthfulness of something because it was only through his passion for art making – combined with the deeper sense of purposefulness he derived from creating work based on the story of his life and those in his community – that he was able to survive and even thrive in conditions I’m sure would have killed anybody else.

Based on this, I would agree with Peter that art does definitely matter more than the mess. That said, and considering how much the mess threatened to destroy both Peter’s life and his art, I think both are important.

Often after watching documentaries, people feel moved to take action or get involved in some way. What were and are you hoping for in terms of your film’s impact?

I didn’t think about what impact I wanted our film to have while we were making it. All I wanted during that time was for Peter to not die alone with all of his art buried in the decrepit house he was “living” in. Only upon completing the film have I been able to see the impact it has on others – not just on various art communities but also on anyone who is confronting issues involving poverty, the elderly, the disabled, and those with mental illness. Peter’s story may be extreme, but it is ultimately universal: most everyone has a friend, relative or neighbor who mirrors some of Peter’s eccentricities, and sooner or later, everyone copes with end-of-life issues with a parent or grandparent. And we can all relate to the difficulty of letting go, as well as the fear of making long-term changes, even when those changes may be for the better.

While our film also explores the how’s and why’s of compassion, as well as the limits of altruism, it more specifically provides a portrait of what aging is like for many people in America who have no family members left and currently live at or below the poverty level. Several people have approached us after screenings to tell us how much they hope every elderly person – and every person taking care of someone who is elderly – will see what we’ve made.

What would your playlist of documentary favorites consist of?

My list of doc favorites would be way too long to share in its entirety here, so I’ll instead highlight some of my favorites that were particular inspirations during the making of Almost There. Three are from our amazing production collective Kartemquin Films: Stevie, Home For Life, and Golub: Late Works are the Catastrophes. Other fantastic films I thought about a lot while making our film include: Grey Gardens, Marwencol, Crumb, American Movie, Little Dieter Needs to Fly, Mr. Dial Has Something to Say, and last but not least, The Devil and Daniel Johnston.

________________

ALMOST THERE is Influence Film Club’s featured film for December. Each month Influence Film Club hand-picks one of our favorite docs as our club’s featured film to watch and discuss together. Throughout the month, starting with our newsletter and continuing on our website and social media we will extend the conversation by exploring the various issues touched on in the film, providing filmmaker interviews, suggesting ways to Influence, and discussing documentaries in general – because after all, We Love Docs.

Interview by: Julia Bier

The path he followed led him from snacking on leftovers at one of LA’s production houses to Chicago’s documentary powerhouse, Kartemquin. Would acclaimed editor and co-director of our December film, ALMOST THERE, Aaron Wickenden have thought he was going to have the career he has today when he was cracking the crust of crème brûlée in the mecca of film? It’s hard to know. But one thing is clear: not quite getting what you set out for, as the film’s title suggests, does not apply to Aaron. Amongst his several award winning collaborations are films like Oscar shortlisted Best of Enemies by Morgan Neville who described Aaron with the following words: “Docs, in general, are made in the edit bay, archival docs even more so… We brought in Aaron Wickenden, who cut Finding Vivian Maier, and he’s amazing.” See it for yourself!

What is it that draws you to documentary film?

The collaborative storytelling process is a big part of it… and with that, the joy that comes from working in small groups of passionate people. When I graduated from college in 2000 my work experience was the opposite to the career in documentary that I have now. I went to work at a major post production house in Los Angeles. I told the HR director I wanted to be an Assistant Editor. Instead I was assigned to the Client Services team where I would spend the next few months bringing espresso drinks and crème brûlées to advertising executives and show runners. After I mastered that, they promoted me to the Tape Vault where I put barcodes on film and tape elements and made sure they didn’t get lost in FedEx. It was a fun gig at first because I could zone out, eat crème brûlée leftovers and listen to KXLU while getting my work done. After a while it occurred to me that what I was doing had so little to do with the actual films and shows that we were working on that I might as well have been selling t-shirts. Nowadays, the teams I work on are usually about 3-5 people at the core: Director, Producer, Editor, and if I’m lucky an Associate Producer and Assistant Editor. The creative conversations I get to participate in at that level are fantastically stimulating.

You have worked as an editor on many films, including Finding Vivian Maier and The Interrupters. Can you tell us about your history with documentaries? In what way was it different from your previous experiences to work as a co-director on Almost There?

During college, one of my best and hippest friends turned me onto the radio show This American Life. It was early in that show’s history and I remember sitting in my friend’s loft in Tucson sparking off of all of these great stories and drinking lots of wine. Around that same time I stumbled across a copy of Kartemquin’s classic film Inquiring Nuns on VHS at my college’s library. That film blew my mind. Essentially the film is about two nuns walking around the streets of Chicago in 1968 asking people if they were happy. It features one of the first film scores by Phillip Glass who was a student at the University of Chicago. These experiences were among the first that sent me on my way towards docs.

In the winter of 2001, after moving to Chicago myself, I came across another copy of Inquiring Nuns at a great video store called Facets. I looked up Kartemquin online but at that time their website was really terrible and had no contact information. So I grabbed a phone book, found their listing and called to see if they had an internship program. The timing couldn’t have been better because Kartemquin was in the midst of creating a 7 hour mini-series for PBS called The New Americans and they needed all the help they could get. Another turning point in my career happened then because I met Steve James. He was incredibly kind, approachable, and sincere while also being very funny. He went on to hire me as his Assistant Editor on Reel Paradise which we premiered at Sundance in 2004. In a way, I was mentored by Steve over the years and he quickly promoted me up the post-production ladder to the point where we co-edited two films: At the Death House Door (2008), and The Interrupters (2011).

Only in the past few years I have started working with other directors and I’ve been very lucky to have some great filmmakers come my way. The resulting success of films like Finding Vivian Maier, The Trials of Muhammad Ali, and Best of Enemies only continues to help open my world up to new creative collaborations. Each experience is very different. The most different of which would be Almost There because I was co-directing and producing it with my talented friend Dan Rybicky. I was also the cinematographer, editor, and a minor character in the film. After completing Almost There I think I understand a bit better how exhausting it is to direct a documentary and push it out into the world. As a result I now have an expanded depth of compassion for my directors and the stresses they’re navigating.

You shot the film over the course of 8 years. How did you manage to keep control over the presumably extensive amount of footage? How do you find a starting point?

I’m pretty methodical and system oriented when it comes to my projects. However by contrast, my office is usually a mess and I wish I could declutter my living space with the same rigor that I do with my films. It’s one of my 5 year goals.

With Almost There we certainly had a mountain of footage that accumulated over the years. It was all organized by shoot date and then backed up onto multiple drives in case one of them failed. I still have eight external hard-dives hooked up next to my computer at home so that I can finish and deliver our TV version of the film which has to be about 56 minutes long. Believe me, I am looking forward to boxing up those drives and putting them into storage.

If we had just tried to attack the edit of the film by just diving in I think we would have failed miserably. We actually started by writing and submitting proposals to ITVS [Independent Television Service] as part of their Open Call process that can result in a TV acquisition. We applied 3 times before being successfully funded, and with each application our written description would get tighter and more refined. ITVS gave us feedback as we went along and it helped us understand how to tell our story. Once successfully funded we were faced with a new challenge: could we pull off what we had written in our proposal.

Though he certainly doesn’t appear as the easiest person to deal with, Peter Anton’s story is heart-wrenching and while watching the film you can’t help thinking how lucky he was to meet you and Dan. What does Almost There really mean to Peter and how is he doing today?

When we first met Peter he was living in a pretty horrible situation where his home was falling down around him and he had self-isolated from his community. Those were the conditions that compelled Peter to want to chronicle his life story. In writing about himself, I think he wanted to cultivate a certain kind of control and self-worth that he didn’t feel in his day-to-day life. He began making his scrapbooks in the early 1980s and by the time he was finished there would be 13 volumes comprising his life-story, Almost There. He explained to us that this title choice came from his life being composed of “almost there” experiences where he was close to succeeding but didn’t quite make it.

Now that Peter is out of his home, the film is out in the world, and he has reconnected with a community it’s clear that his compulsion to tell his life story has calmed down. He’s now working on other artistic pursuits: directing an elderly person’s choir, writing a massive book of facts about the world, and teaching art classes. He’s very fulfilled by these things.

The other day a very favorable review of our film came out in The Chicago Tribune. Peter read it and called me. He thought it was interesting but all he really wanted to do was to talk about how we were going to get his new book published. So he’s basically over the film… and that’s amazing.

Thinking of filmmaking as the art form it is, in what way has Peter’s story influenced your own pursuits as an artist?

My favorite art of Peter’s comes from a place of his compulsion. It’s work he has to make no matter what. As a freelance editor for hire, I try to chose to work with directors who feel that same need to make their film. I also try to judge how acutely I’m catching this contagious need for the film to be made. If I find myself wanting to tell my friends about a new project I’m working on and I can feel myself getting excited while I’m talking about the film, then those are good signs for its success. When those things aren’t in play, I’ve found that the purpose for the film existing in the world can get kind of diluted, the director can loose steam and the work becomes more of a job then a collaborative art. In those instances it’s still a wonderful job to have, and I’m lucky to be paid to be creative…but at the end of the day I’m in it for the process and want to be around people who are excited.

What has been the primary conversation you have observed people are having around the film? Has it stirred up some strong opinions?

When people watch the film it reminds them of conversations they’ve had with a family member or neighbor around moving out of their home and whether a nursing home is the right fit for them. While Peter is going though a pretty extreme version of this transition in our film, this pivotal time in a person’s life is very relatable. We’ve now shown the film at over 30 film festivals around the world and I’ve noticed people consistently leave the theater with a sense of expanded compassion towards the elderly. If that is the legacy of this film than I’m pretty happy with the outcome of this whole endeavor.

What are your 6 favorite documentaries of all times?

________________

ALMOST THERE is Influence Film Club’s featured film for December. Each month Influence Film Club hand-picks one of our favorite docs as our club’s featured film to watch and discuss together. Throughout the month, starting with our newsletter and continuing on our website and social media we will extend the conversation by exploring the various issues touched on in the film, providing filmmaker interviews, suggesting ways to Influence, and discussing documentaries in general – because after all, We Love Docs.

Interview by: Julia Bier

Thank you everyone for an incredible festival!

What a joy to meet with such an engaged audience and the incredibly talented filmmakers below.

Film pages will be coming soon for all of the films we discussed at the club.

Thank you:

Director Jerry Rothwell of “How to Change the World”, Directors Aaron Wickenden and Dan Rybicky of “Almost There” and Tim Horsburgh, Director of Communications and Distribution at Kartemquin Films, Director Leslee Udwin of “India’s Daughter”. Director Laura Nix of “The Yes Men are Revolting”, Director Kirby Dick of “The Hunting Ground”, Director Louise Osmond of “Dark Horse”, and of course The Sheffield Doc/Fest Crew

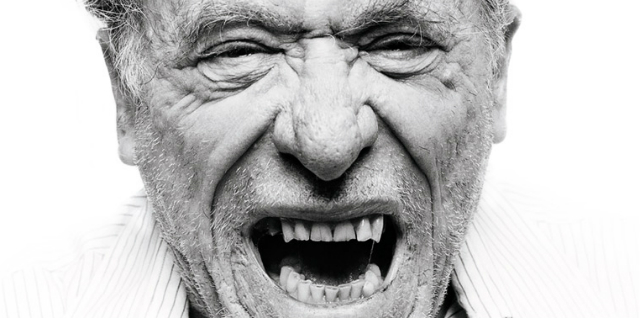

“You’ve got to burn straight up and down and then maybe sideways for a while and have your guts scrambled by a bully and the demonic ladies, you’ve got to run along the edge of madness teetering, you’ve got to starve like a winter alleycat, you’ve go to live with the imbecility of at least a dozen cities, then maybe maybe maybe you might know where you are for a tiny blinking moment.” – Charles Bukowski

Much like Bukowski himself, who spent much of his 73 years in the crazed haze of an alcohol infused fervor, enduring the whoas and joys of a starving artist with the emotional and creative extremes that come with such a provocative lifestyle, artists throughout history have often embraced all forms of madness in hopes of harnessing wild eyed authenticity in the name of art and purpose. For many, suffering and beauty are two sides of the same coin.

Non-fiction cinema is packed to the gills with such characters, from the men and women behind the cameras to those who’ve submitted themselves freely to be taken in by our watchful gaze. Like the wildly empathetic, grizzly obsessed nature-boy whom lost his life to the jaws of those he so loved in GRIZZLY MAN, the manic-depressive emotionally raw singer/songwriter at the heart of THE DEVIL AND DANIEL JOHNSTON, or the OCD-afflicted world travelling freedom fighter of POINT AND SHOOT, many are propelled to document their own unstable existences, unknowingly reaching out on their own to the anonymous unknown as if the visual documentation of one’s life itself might bring some form of lucidity to an otherwise mad caper. As we see, autobiography doesn’t seem to make their journey through life any easier, yet they continue nonetheless.

Others merely embrace their lunacy, knowing all along that their life’s endeavors are those of idealistic moonstruck dreams. The tightrope walker of MAN ON WIRE damns all logic, personal safety, and even legality in an act of singularly spectacular physical performance, while the abiding filmmaker of AMERICAN MOVIE, eyes deep in debt and personal crises, obsessively crusades in the name of his perfect picture. And much like Bukowski himself, the starving outsider artist at the center of ALMOST THERE has lived a life fueled and haunted by mental volatility in the pursuit of artistic revelation. Sometimes one must let go of reason and stability to reach out for something greater.

The following six films bring us closer to that “edge of madness” that Bukowski so lovingly speaks of, allowing us a view of the world detached from logic through the eyes of dreamers and madmen.

Man on Wire

MAN ON WIRE explores tightrope walker Philippe Petit’s daring, but illegal, high-wire routine performed between the twin towers of New York City’s World Trade Center in what some consider “the artistic crime of the century”.

Grizzly Man

In GRIZZLY MAN Werner Herzog explores the life and death of Timothy Treadwell who lived among the grizzly bears of Alaska for 13 consecutive summers until being attacked and eaten by a bear in 2003.

Almost There

For filmmakers Rybicky and Wickenden, Peter Anton’s home is a treasure trove, a startling collection of unseen and fascinating paintings, drawings, and notebooks, not to mention Anton himself. ALMOST THERE is a remarkable journey following a gifted artist through startling twists and turns.

American Movie

The story of filmmaker Mark Borchardt, his mission, and his dream. Spanning over two years of intense struggle with making a movie, family issues, financial decline, and personal crisis, AMERICAN MOVIE is a portrait of ambition, obsession, excess, and one man’s formidable quest for the American Dream.

Point and Shoot

With a gun in one hand and a camera in the other, 28-year-old OCD-afflicted Matthew VanDyke set off on a 35,000-mile motorcycle trip through Northern Africa and the Middle East, where he undergoes a self-described “crash-course in manhood.”

The Devil and Daniel Johnston

THE DEVIL AND DANIEL JOHNSTON follows the long and winding road traversed by Daniel Johnston – manic-depressive singer/songwriter/artist – on his way from childhood to manhood in this portrait of madness, creativity and unrequited love.