Music plays an instrumental role in each and every one of our lives. The opening seconds of a song can stir up an entire range of emotions, catapulting us back to that first kiss or the feel of the breeze in our hair on that summer boat ride. In the midst of a winter storm, a breezy melody can transport us to the soft sands of a tropical beach. With its sonic strength, music interlaces itself deep into the fabric of our memory and offers a bridge back to the places, people, and passions of our past. We all know that music and memory are intertwined, yet witnessing exactly how intertwined they are can still surprise us.

After being moved by the work of social worker Dan Cohen while shooting a few short videos for a website, director Michael Rossato-Bennett fearlessly followed the founder of the nonprofit organization Music & Memory as he struggled against a tired healthcare system to inject the healing powers of music into the lives of individuals suffering from dementia and Alzheimer’s – resulting in our touching and beautiful film of the month for March, ALIVE INSIDE.

What is it that drew you make “Alive Inside”?

A friend of mine asked me to do it, to build a website with some films in it for a social worker named Dan Cohen. There was a tiny bit of money, and I did it as a job. I got my equipment and my crew, and we went into this 600 bed nursing home, and there was Dan. and there was Dan. He was trying to spread his idea of bringing personalized music to elders. And he wasn’t having a tremendous amount of luck spreading the idea, so we thought if we could show what he was doing, that might help him. That was it.

When you make a documentary film, you shoot, and you shoot, and you shoot, and sometimes, suddenly, a moment happens- and it brings a tear to your eye. You know you’ve hit something, something real- that your instinct, or whatever it was that set you down this path of shooting, was correct. You have a film! In this case, we went into the hospital, down these corridors of sadness. Here I am, I’m a free and unfettered human being, and I’m walking down these corridors of these silent and shut-off people, literally just waiting.

We go into this room, and see this man–literally a blob in a chair, entirely collapsed in on himself, as inward as he possibly could be, divorced from the outer world. Dan puts a pair of headphones on him, and starts to play the music from when he was young, from 80 years ago, when his soul was just forming. I’m filming, watching this man as he, slowly, sort of come to life- starts singing, and when that happens a chill runs up my spine. It is like seeing Lazarus, a man rising from the dead. And it doesn’t stop, we take the headphones off him, and all of a sudden he is speaking to us in poetry, and singing to us in a voice that is so full of wisdom, so beyond my own.

And I have tears in my eyes. I cried five times that first day of shooting. And I said right there, “Okay, that’s it, this is my next film.” I didn’t have to find “a moment” – it was right here, in front of me. If it hits me like this, there is something here that needs to be told. If there is this much life hidden in these people, if all it takes a little sprinkle of their own past, their own humanness, to awaken this kind of life and poetry, this is where I belong!

Is there a red thread that has followed you throughout your career as a documentary filmmaker and in other pursuits?

The red thread of my career is awakening. I think we are dangerously asleep. Wake up! lets find a better path!

My skills are that I’m kind of fearless in a way, that’s my whole skill set really. I live my whole life sort of without a safety net, if you will. It gives me a kind of freedom. As a documentary filmmaker, your freedom and your allegiance, these are your true allies. So, for me, my freedom and my allegiance are deeply intertwined.

My allegiance is to that unknown place, that is a part of everyone, that seems to inform all of the best things we do. And so, if you ask me what my work is, I suppose I should say that on every level of my life, including my positions on artistic, political, and social issues, it’s seeking that place. And that is actually what has given what I do some legs- the capacity to touch people. And I’ve found personally, that the deepest, safe thing that you find: that will give you the most nourishment.

The film is very touching, specifically because it deals with the subject of elderhood, connection and memory, subjects we rarely discuss yet many of us fear. What has been the primary conversation you have observed people are having around the film? Has it stirred up some strong opinions and feelings?

We’ve become a tremendously fractured communal being. We’ve separated ourselves from our deepest sources of inspiration and justice, and intelligence, perhaps. So, my artistic and social experiments are based on trying to hit notes that are deeply within our consciousness, that ring. Alive Inside; it’s a film about death, it’s about dying, it’s about Alzheimer’s disease, but that’s ok, it hits something.

A friend of mine said, “You’re making a film about death, dying, and old age: my three least favorite subjects in the world.” And I was like, “Yes, that’s true! they are everyone’s least favorite subjects!”

But this is the key, the key that I’ve found, the choice I’ve made in this endeavor that made all the difference, to go through the door of music and emotion. See, when you seek through music and emotion, it enters humans in a place where it is a reality beneath the mind. And so, people are able to, in my experience, people have been able to open themselves to questions that they usually hide from. Questions that our entire society banishes–literally hides in the darkest corners of our subconscious, attempts to push into the unconscious.

I guess I’m just trying to shine a light on things that are inescapable and interconnected, and I find this in emotion and in music, powerfully.

The film is strangely not disturbing. There are so many messages we get in this culture about division, yet this film is about connection, and it really opens people’s hearts up. I love talking to audiences after they see it. They are very beautiful and open with the parts of their being they don’t usually linger in. I find them both grateful and happy to sit in those places within themselves. My hope is they have to courage to change life for someone. People write me every day to tell me the story of the magic of music and the mind.

Often after watching documentaries, people feel moved to take action or get involved in some way. What actions would you recommend people take after watching “Alive Inside”?

I would recommend visiting aliveinside.org to find out how you can engage further – there you can support the Alive Inside Foundation with a donation, sign up to volunteer or get engaged, and learn about how to make a playlist for someone close to you using the AIF Memory Detective App.

The film is truly a call to action – what were your goals and what kind of impact has the film had? Has anything occurred that has left you with the feeling “this is why we made this film”?

I want to help make the dream of returning connection, aliveness and music to our elders come true. There’s so many people in nursing homes, and, a couple million out of sight, and I can’t tell you how many letters I’ve gotten from people telling me ‘oh my god this is so beautiful, I wish I had seen this before my father passed…’ or even sadder, people say, ‘If I had only known, my father was a composer, he played piano his whole life, and I never thought to bring him his music while he was going through his dementia.’ Or the opposite story, ‘oh, thank you for showing this to me. I went in and my father or my mother was sitting like a bump on a log, and I gave her music, and she was happy for a moment, and she came back the way she was three years ago, just for a moment.’ So, we’re just trying our best.

What would your playlist of documentary favorites consist of?

What Happened Miss Simone, The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence, The Cats of Mirikitani, Into the Abyss, and The Wolfpack.

___________________________________________________________

ALIVE INSIDE is Influence Film Club’s featured films for March. Each month Influence Film Club hand-picks one (or two) of our favorite docs as our club’s featured film(s) to watch and discuss together. Throughout the month, starting with our newsletter and continuing on our website and social media we will extend the conversation by exploring the various issues touched on in the film(s), providing filmmaker interviews, suggesting ways to influence, and discussing documentaries in general – because after all, We Love Docs.

Interview by: Isis Graham

A good documentary is just the beginning…

Influence Film Club invites you to three evenings after work- “doc- tails” at Barbro where documentary lovers and documentary filmmakers will have the opportunity to meet each other. Have a drink and take part of in-depth talks about some of the year’s Tempo movies.

The first 20 drinks each evening are on us – so come early!

Wednesday 9/3 at 17:00-18:00:

Influence Film Club discusses Sonita.

NOTE the schedule change: Unfortunately Rokhsareh Ghaem Maghami, director of Sonita, is not able to travel to Stockholm due to passport issues. We’ll still be at Barbro ready to discuss the film and the intersection between art, music, and politics.

Thursday 10/3 at 17:00-18:00:

In conversation with Jerzy Sladkowski director of Don Juan.

Friday 11/3 at 17:00-18:00:

In conversation with the Hussin Brothers, directors of America Recycled.

Moderated by: Isis Marina Graham

Free entrance with Tempo’s membership card!

Hosted in English.

“You’ve got to burn straight up and down and then maybe sideways for a while and have your guts scrambled by a bully and the demonic ladies, you’ve got to run along the edge of madness teetering, you’ve got to starve like a winter alleycat, you’ve go to live with the imbecility of at least a dozen cities, then maybe maybe maybe you might know where you are for a tiny blinking moment.” – Charles Bukowski

Much like Bukowski himself, who spent much of his 73 years in the crazed haze of an alcohol infused fervor, enduring the whoas and joys of a starving artist with the emotional and creative extremes that come with such a provocative lifestyle, artists throughout history have often embraced all forms of madness in hopes of harnessing wild eyed authenticity in the name of art and purpose. For many, suffering and beauty are two sides of the same coin.

Non-fiction cinema is packed to the gills with such characters, from the men and women behind the cameras to those who’ve submitted themselves freely to be taken in by our watchful gaze. Like the wildly empathetic, grizzly obsessed nature-boy whom lost his life to the jaws of those he so loved in GRIZZLY MAN, the manic-depressive emotionally raw singer/songwriter at the heart of THE DEVIL AND DANIEL JOHNSTON, or the OCD-afflicted world travelling freedom fighter of POINT AND SHOOT, many are propelled to document their own unstable existences, unknowingly reaching out on their own to the anonymous unknown as if the visual documentation of one’s life itself might bring some form of lucidity to an otherwise mad caper. As we see, autobiography doesn’t seem to make their journey through life any easier, yet they continue nonetheless.

Others merely embrace their lunacy, knowing all along that their life’s endeavors are those of idealistic moonstruck dreams. The tightrope walker of MAN ON WIRE damns all logic, personal safety, and even legality in an act of singularly spectacular physical performance, while the abiding filmmaker of AMERICAN MOVIE, eyes deep in debt and personal crises, obsessively crusades in the name of his perfect picture. And much like Bukowski himself, the starving outsider artist at the center of ALMOST THERE has lived a life fueled and haunted by mental volatility in the pursuit of artistic revelation. Sometimes one must let go of reason and stability to reach out for something greater.

The following six films bring us closer to that “edge of madness” that Bukowski so lovingly speaks of, allowing us a view of the world detached from logic through the eyes of dreamers and madmen.

Man on Wire

MAN ON WIRE explores tightrope walker Philippe Petit’s daring, but illegal, high-wire routine performed between the twin towers of New York City’s World Trade Center in what some consider “the artistic crime of the century”.

Grizzly Man

In GRIZZLY MAN Werner Herzog explores the life and death of Timothy Treadwell who lived among the grizzly bears of Alaska for 13 consecutive summers until being attacked and eaten by a bear in 2003.

Almost There

For filmmakers Rybicky and Wickenden, Peter Anton’s home is a treasure trove, a startling collection of unseen and fascinating paintings, drawings, and notebooks, not to mention Anton himself. ALMOST THERE is a remarkable journey following a gifted artist through startling twists and turns.

American Movie

The story of filmmaker Mark Borchardt, his mission, and his dream. Spanning over two years of intense struggle with making a movie, family issues, financial decline, and personal crisis, AMERICAN MOVIE is a portrait of ambition, obsession, excess, and one man’s formidable quest for the American Dream.

Point and Shoot

With a gun in one hand and a camera in the other, 28-year-old OCD-afflicted Matthew VanDyke set off on a 35,000-mile motorcycle trip through Northern Africa and the Middle East, where he undergoes a self-described “crash-course in manhood.”

The Devil and Daniel Johnston

THE DEVIL AND DANIEL JOHNSTON follows the long and winding road traversed by Daniel Johnston – manic-depressive singer/songwriter/artist – on his way from childhood to manhood in this portrait of madness, creativity and unrequited love.

After more than a decade of filming in Indonesia, director Joshua Oppenheimer left the country, knowing that he would probably not be able to come back. He brought away the material for two of the most outstanding documentaries of our time, THE ACT OF KILLING and THE LOOK OF SILENCE, our featured films for February. Two films that have the immense power to change the dynamics of a culture by lifting the veil on the daily horrors many Indonesians experience still today because of the 1965 genocide that forever changed their lives. The haunting first film lets the perpetrators speak, leaders of present Indonesian society, eager to reveal their “heroic” acts of killing; in the 2015 companion piece Oppenheimer quietly tells the story about the incredible act of surviving in the face of deeply rooted trauma and bone harrowing terror. Through his work, the survivors have the final say, but now we hand over to the Oscar-nominated filmmaker himself.

What is it that draws you to documentary film?

It is a life practice that allows me to explore the deepest mysteries in human life and perception, and sculpt what I find into an immersive, poetic experience for an audience, a translation of what I discover through the journey of filmmaking.

What is your own history with documentaries? Is there a red thread that has followed you throughout your career?

I think the dominant theme in my work has been pretence and self-deception. By giving people a stage on which they can dramatize their lives, memories, and feelings, I return to the state-of-nature of nonfiction filmmaking: the simple fact that whenever you point a camera at anybody, they start acting out idealized images of themselves, how they want to be seen, how they see themselves. These self-understandings are always informed by fictions, by second-hand, third-rate stories borrowed from the cinema, television, advertising. That is, we make ourselves and our world through fictions. Rather than rush past the self-consciousness that is inevitable when people are filmed, we should work with this self-consciousness, allowing people to make their fantasies about who they are in the world explicit, and creating occasions where people confront those fantasies. In this way, the nonfiction camera becomes a prism that makes visible the myriad fictions that constitute our ‘factual’ reality. I have always been interested in what happens when these fiction scenes are allowed to take over a film’s form. What fever dreams become possible? This is why I tend to refer to my work as nonfiction rather than documentary – I’m trying to avoid the sobriety and journalistic connotations that ‘documentary’ has in the English language.

Rather than pretend to be a fly on the wall, I would rather collaborate with my participants to create occasions that make visible the previously invisible forces responsible for the problems I’m investigating. This is always a transformative moment: in order to function, these forces have depended upon their invisibility. The moment they are made explicit and visible, everything changes – in ways analogous to The Emperor’s New Clothes. People – participants and the audience – can suddenly talk about the forces shaping their lives in ways they could not before.

Many people describe THE ACT OF KILLING as a “game changer” for the documentary genre – why do you think this is? And where do you think the genre is headed?

Building on what I said above, I think the 159-min uncut version of THE ACT OF KILLING – 40 minutes longer than the US theatrical release – is not a documentary at all, but something new, a fever dream, because the fiction scenes created by Anwar Congo and his friends completely take over the film’s form. The uncut “Act of Killing” uses its extra run-time to do a deeper, more profound work – something surreal and dreamlike that viewers may not have experienced before. It is punctuated by moments of absolute silence, pauses that give the viewer space to rest, recover to take in the surreal material – and that makes it feel more real, and consequently more important. The story unfolds more gradually, to a more intimate rhythm, and grows bigger in scope. It offers more time to get close to the characters, to better understand their development. This makes it a gentler, more intimate, and more profound experience.

The uncut version gives viewers time (and extra scenes) to feel Anwar’s evolving doubt, and get lost with him in his nightmares. These begin simply as his bad dreams, but they grow to embody the nightmare of a man living with mass murder on his conscience. They grow further to encompass the nightmare of humanity itself living with genocide and blindness as the foundation of our everyday normality. And as the nightmare grows, Anwar and his friends’ fiction scenes reveal poetic truths deeper than the observational documentary material. The boundaries between fiction and documentary blur. The fiction scenes takes over the film’s form, unmooring it, sending it spiraling into a surreal fever dream. Most significant, though, is the end of the film. In the final act, Anwar’s descent is more complex and honest in the uncut film: his anger and sadism return with a vengeance — and in response to growing regret. Remorse is painful, and the pain makes him angry. He takes it out on his victims, until he finally experiences a shattering, physical recognition of what he has done.

Note that the uncut “Act of Killing” is available in the US on Netflix and DVD as “The Act of Killing – director’s cut”, though this is misleading as director’s cuts are usually made afterwards, and out of regret. The 159-min version is, in fact, the original unabridged film — the full culmination of our eight-year journey making it. It was the main festival and cinema version outside the US, and received the majority of the film’s accolades.

It’s hard to put into words what kind of strange, disturbing feeling it was to watch men who have committed horrible crimes strolling around and describing what they did, often even laughing and smiling. How did you gain their trust and what were your feelings working closely with perpetrators like Anwar?

It took nothing to get them to open up about their crimes. When Adi Rukun, the protagonist of THE LOOK OF SILENCE, asked me to approach the perpetrators back in 2003, I was afraid it would be dangerous. But each perpetrator was immediately open and boastful about the most grisly details of what they’d done. What was harder was getting them to open up about their feelings. Yet once Anwar revealed that he suffered from nightmares as a result of what he’d done, I used this as my opportunity to tell him that I was also haunted by the terrible stories he was telling me. From that point on, I was very open with Anwar about my feelings, though I showed him at every moment that I regard him as a human being. I think this came as a relief to Anwar: he realized that this was a safe space to begin exploring his guilt. Normally, he does not dare acknowledge his feelings of guilt because he isn’t sure how he could continue to live with himself. But with me he saw that he could admit he did wrong (even if only through his body language, his subtext, his description of his dreams), and I would continue to see him as a human being. In a way, Adi Rukun does the same thing: by testing the perpetrators’ eyes, he shows them that he sees them as human, that he’s trying to help them see, and in an intimate way. This helps them open up to him.

I refused to comfort myself by telling myself that these men are monsters, and I am somehow fundamentally different from them, cut from different cloth. And having made this refusal, I bore the responsibility of approaching them as a human being, naked, in a way, entering the darkness of what it must be like for them to live with such horrors on their conscience. And I entered this space refusing to flinch. This was emotionally difficult for me and my crew.

There’s a sequence in the Director’s Cut of THE ACT OF KILLING where Anwar butchers a teddy bear in a film noir scene; it is one of the most important scenes in the movie to me, because Anwar is despairingly embracing the guilt he begins to realize he can never escape. While we were filming it, Anwar stopped the action to tell me that I was crying. I hadn’t realized it. This was the only time I’ve ever cried without knowing I was crying. Anwar asked, “What should we do? Shall we stop?” I said, “We must continue.” In a way I wish I’d stopped, because I went home that night and had terrible nightmares. Indeed, that was the beginning of eight months’ insomnia and nightmares… THE ACT OF KILLING was emotionally frightening to make, while THE LOOK OF SILENCE was emotionally healing. And at the end of it all, I feel I have overcome that most crippling fear of all: the fear of looking.

You said that Adi, the protagonist of THE LOOK OF SILENCE, asked you to approach the perpetrators in THE ACT OF KILLING. Can you explain about the timeline of the two films, how they came to be, and your decision to create two separate works?

I first went to Indonesia in 2001 to help oil palm plantation workers make a film documenting and dramatizing their struggle to organize a union in the aftermath of the US-supported Suharto dictatorship, under which unions were illegal. In the remote plantation villages of North Sumatra, one could hardly perceive that military rule had officially ended three years earlier. The conditions I encountered were deplorable. Women working on the plantation were forced to spray herbicide without protective clothing. The mist would enter their lungs and then their bloodstreams, destroying their liver tissue. The women would fall ill, and many would die in their forties. When they protested their conditions, the Belgian-owned company would hire paramilitary thugs to threaten them, and sometimes physically attack them.

Fear was the biggest obstacle they faced in organizing a union. The Belgian company could get away with poisoning its employees because the workers were afraid. I quickly learned the source of this fear: the plantation workers had a large and active union until 1965, when their parents and grandparents were accused of being “communist sympathizers” (simply for being in the union) and put into concentration camps, where they were exploited as slave labor and ultimately murdered by the army and civilian death squads.

In 2001, the killers not only enjoyed complete impunity, but they and their protégés still dominated all levels of government, from the plantation village to the parliament. Survivors lived in fear that the massacres could happen again at any time. After we completed the film (The Globalisation Tapes, 2002), the survivors asked us to return as quickly as possible to make another film about the source of their fear – that is, a film about what it’s like for survivors to live surrounded by the men who murdered their loved ones, men still in positions of power. We returned almost immediately, in early 2003, and began investigating one 1965 murder that the plantation workers spoke of frequently. The victim’s name was Ramli, and his name was used almost as a synonym for the killings in general.

I came to understand the reason this particular murder was so often discussed: there were witnesses. It was undeniable. Unlike the hundreds of thousands of victims who disappeared at night from concentration camps, Ramli’s death was public. There were witnesses to his final moments, and the killers left his body in the oil palm plantation, less than two miles from his parents’ home. Years later, the family was able to surreptitiously erect a gravestone, though they could only visit the grave in secret.

Survivors and ordinary Indonesians alike would talk about “Ramli,” I think, because his fate was grim evidence of what had happened to all the others, and to the nation as a whole. Ramli was proof that the killings, no matter how taboo, had, in fact, occurred. His death verified for the villagers the horrors that the military regime threatened them into pretending had never occurred, yet threatened to unleash again. To speak of “Ramli” and his murder was to pinch oneself to make sure one is awake, a reminder of the truth, a commemoration of the past, a warning for the future. For survivors and the public on the plantation, remembering “Ramli” was to acknowledge the source of their fear – and thus a necessary first step to overcoming it. And so, when I returned in early 2003, it was inevitable that Ramli’s case would come up often. The plantation workers quickly sought out his family, introducing me to Ramli’s dignified mother, Rohani, his ancient but playful father, Rukun, and his siblings – including the youngest, Adi, an optician, born after the killings.

Rohani thought of Adi as a replacement for Ramli. She had Adi so she could continue to live, and Adi has lived with that burden his whole life. Like children of survivors all across Indonesia, Adi grew up in a family officially designated “politically unclean,” impoverished by decades of extortion by local military officials, and traumatized by the genocide. Because Adi was born after the killings, he was not afraid to speak out, to demand answers. I believe he gravitated to my filmmaking as a way of understanding what his family had been through, a way of expressing and overcoming a terror everybody around him had been too afraid to acknowledge.

I befriended Adi at once and together we began gathering other survivors’ families in the region. They would come together and tell stories, and we would film. For many, it was the first time they had publicly spoken about what happened. On one occasion, a survivor arrived at Ramli’s parents’ home, trembling with fear, terrified that if the police discovered what we were doing, she would be arrested and forced into slave labor. Yet she came because she was determined to testify. Each time a motorcycle or car would pass, we would stop filming, hiding what equipment we could. Subject to decades of economic apartheid, survivors rarely could afford more than a bicycle, so the sound of a motor meant an outsider was passing. The Army, which is stationed in every village in Indonesia, quickly found out what we were doing and threatened the survivors, including Adi’s siblings, not to participate in the film. The survivors urged me, “Before you give up and go home, try to film the perpetrators. They may tell you how they killed our relatives.” I did not know if it was safe to approach the killers, but when I did I found all of them to be boastful, immediately recounting the grisly details of the killings, often with smiles on their faces, in front of their families, even their small grandchildren. The contrast between survivors being forced into silence and perpetrators boastfully recounting stories far more incriminating than anything the survivors could have told made me feel as though I’d wandered into Germany 40 years after the Holocaust, only to find the Nazis still in power.

When I showed these testimonials to those survivors who wanted to see it, including Adi and Ramli’s other siblings, everybody said, more or less: “You are on to something terribly important. Keep filming the perpetrators, because anybody who sees this will be forced to acknowledge the rotten heart of the regime the killers have built.” From that point on, I felt entrusted by the survivors and human rights community to accomplish work that they could not safely do themselves: film the perpetrators. All of them would enthusiastically invite me to the places they killed, and launch into spontaneous demonstrations of how they killed. They would complain afterwards that they had not thought to bring along a machete to use as a prop, or a friend to play a victim. One day, early in this process, I met the leader of the death squad on the plantation where we had filmed The Globalisation Tapes. He and a fellow executioner invited me to a clearing on the banks of Snake River, a spot where he had helped murder 10,500 people. Suddenly, I realised he was telling me how he had killed Ramli. I had stumbled across one of Ramli’s killers. I told Adi about this encounter, and he and other family members asked to see the footage. That was how they learned the details of Ramli’s death.

For the next two years, from 2003–2005, I filmed every perpetrator I could find across North Sumatra, working from death squad to death squad up the chain of command, from the countryside to the city. Anwar Congo, the man who would become the main character in THE ACT OF KILLING, was the 41st perpetrator I filmed.

I spent the next five years shooting THE ACT OF KILLING, and throughout the process Adi would ask to see the material we were filming. He would watch as much as I could find time to show him. He was transfixed. Perpetrators on film normally deny their atrocities (or apologize for them), because by the time filmmakers reach them they have been removed from power, their actions condemned and expiated. Here I was filming perpetrators of genocide who won, who built a regime of terror founded on the celebration of genocide, and who remain in power. They have not been forced to admit what they did was wrong. It is in this sense that THE ACT OF KILLING is not a documentary about a genocide 50 years ago. It is an exposé of a present-day regime of fear. The film is not a historical narrative. It is a film about history itself, about the lies victors tell to justify their actions, and the effects of those lies; it is a film about an unresolved traumatic past that continues to haunt the present.

I knew from the start of my journey that there was another, equally urgent film to make, also about the present. THE ACT OF KILLING is haunted by the absent victims – the dead. Almost every painful passage culminates abruptly in a haunted and silent tableau, an empty, often ruined landscape, inhabited by a single lost, lonely figure. Time stops. There is a rupture in the film’s point of view, an abrupt shift to silence, a commemoration of the dead, and the lives pointlessly destroyed. I knew that I would make another film, one where we step into those haunted spaces and feel viscerally what it is like for the survivors forced to live there, forced to build lives under the watchful eyes of the men who murdered their loved ones, and remain powerful. That film is THE LOOK OF SILENCE.

Apart from the older footage from 2003–2005 that Adi watches, we shot THE LOOK OF SILENCE in 2012, after editing THE ACT OF KILLING but before releasing it – after which I knew I could no longer safely return to Indonesia. We worked closely with Adi and his parents, who had become, along with my anonymous Indonesian crew, like an extended family to me. Adi spent years studying footage of perpetrators. He would react with shock, sadness and outrage. He wanted to make sense of that experience. Meanwhile, his children were in school, being taught that what had happened to them – enslavement, torture, murder, decades of political apartheid – all of this was their fault, instilling them and other survivors’ children with shame. Adi was deeply affected – and angered – by the boasting of the perpetrators, his parents’ trauma and fear and the brainwashing of his children.

In early 2010, as I finished filming THE ACT OF KILLING, I gave Adi a video camera to use as a notebook to search for metaphors that might inspire the making of The Look of Silence. When I returned to Indonesia to make the film in 2012, I asked Adi how we should begin. He told me that he had spent seven years watching my footage of the perpetrators, and it had changed him. He wanted to meet the men who murdered his brother. I refused immediately. It would be too dangerous, I told him. For a victim to confront a perpetrator in Indonesia is all but unimaginable. There has never been a nonfiction film, in the history of cinema, where survivors confront perpetrators who still hold a monopoly on power. In response, Adi took out the camera I had given him, and one cassette. “I never sent you this tape,” he explained, “because it is meaningful to me.” Trembling, he put the tape in the camera, pressed play, and began to cry. On the camera’s flip screen came the one scene in the THE LOOK OF SILENCE that Adi shot: the scene at the end in which his father, Rukun, lost in his own home, is calling for help as he crawls from room to room. Through his tears, Adi explained: “This was the first day my father could not remember me, my siblings, or my mom. All day, he was lost, calling for help, but when we tried to help we only made him more frightened, because we had become strangers to him. It was unbearable not to do anything, and after hours of this, not knowing what else to do, I picked up the camera and filmed, asking myself why I am filming? But then I understood: this is the day it became too late for my father to heal. He has forgotten the son whose murder ruined his family’s life, but he has not forgotten the fear. Now that he cannot remember what happened, he will never work through, grieve, mourn. He will die with this fear, like a man locked in a room who cannot even find the door, let alone the key.”

We watched the footage in silence. When it was finished, Adi said, “I do not want my children to inherit this prison of fear from my father, my mother, and from me.” He told me that if he were to visit the men without anger, showing that he is willing to forgive if they can take responsibility for what they have done, they would greet his visit as a long-awaited opportunity to stop their manic boasting and accept their guilt, to find forgiveness from one of their victim’s families. In this way, Adi hoped to live with them as human beings, as neighbors, rather than perpetrators and victims, always afraid of each other. Discussing this with my Indonesian crew, we realized that the shooting of THE ACT OF KILLING was famous across North Sumatra, but nobody had seen it yet. I was therefore well known across the region for having worked closely with the most powerful perpetrators in the country – the Vice President, cabinet ministers, the national head of the paramilitary organisation. The men Adi hoped to confront were regionally but not nationally powerful. They would think I am close to their superiors, and would not want to offend them by physically attacking us or even detaining us. Thus, the unique situation of having shot a film like THE ACT OF KILLING – but not releasing it yet – might allow us to do something unprecedented.

I also realized we were unlikely to get the apology for which Adi was hoping, and I told him so. But I felt that if I could show why the perpetrators cannot apologize, if I could film with precision and intimacy their complex, human reactions to being visited by their victim’s brother, then perhaps I could make visible the abyss of fear, guilt, and (for the perpetrators) fear of their own guilt that divides every Indonesian from each other, and from their own past – and thus from themselves. I told Adi that by documenting the perpetrators’ inability to apologize, maybe we could show how torn the social fabric of Indonesia is. Anybody seeing the film, I hoped, would have to support truth, reconciliation, and some form of justice. In this way, I hoped that, through the film as a whole, we might succeed in a bigger way where we fail in the individual confrontations.

Finally, I realized that whatever truth and reconciliation might come in the future – perhaps, in part, as a consequence of our two films – Adi is right: it is too late for Adi’s father. This film should honor that, and thus must be more than a %9

Between having more than 200,000 followers on social media, holding the number one slot on Australian iTunes, and becoming second highest-grossing documentary with a theatrical release Down Under – our January documentary treat THAT SUGAR FILM has certainly hit its sweet spot. A list of successes like the above doesn’t come out of nowhere, it’s the result of a hard-working team empowering and challenging us from behind the scenes. Making us kick our sugar addiction and get hooked on THAT SUGAR FILM instead, Anna Kaplan plays an exciting role that is forming, shaping and increasingly becoming recognized within the world of documentary filmmaking: the Impact Producer. She is helping bring our film of the month to the world and orchestrate change and now we have the chance to bring her to you.

What is it that draws you to documentary film?

I studied broadcast journalism, but I was drawn to documentary because I always wanted to delve deeper into stories and follow them over a longer period than a news story allowed. I get really excited by bold, cinematic films that play with the form and push the boundaries, but at heart I’m a sucker for a good observational film that follows quirky characters doing inspiring or unconventional things. I love the way documentaries allow filmmakers to challenge the status quo and open the audience’s minds to ideas or issues by allowing them to connect emotionally with the film’s subjects.

What is your own history? Is there a red thread that has followed you throughout your career as a documentary producer and in other pursuits?

I’ve worked in documentary production for most of my career, starting out in the BBC’s documentary department in London, before moving to Australia where I started producing documentaries and short films independently and working with other producers in various production roles. I supplemented the paltry income I made from my own projects working on feature films, TV drama series, online and educational projects, but I always have a documentary passion project bubbling away. My work spans a broad range of topics, from ageing, family and motherhood to youth justice, crime, refugees, Aboriginal rights and female empowerment. The red threads would be social justice and ordinary people doing extraordinary things. I feel incredibly privileged to do this work and I get to meet and work with the most amazing people.

For That Sugar Film you work as an Impact Producer. Since this is an increasingly important roll among documentary film teams but at the same time is a rather new term for many, could you explain what your job looks like?

It’s a real mix and draws heavily on my existing skills base as a producer and project manager, such as writing, budgeting, scheduling, project management, content development, audience engagement, legals, grant writing, financial and narrative reporting and liaising with various stakeholders. But it has also required me to develop a new skill set across campaign strategy, corporate partnerships, social media marketing, non-traditional distribution and project evaluation. I’ve also had to learn to frame the outputs and success of the project in a way that ensures that our philanthropic donors and outreach partners are getting a return on their social investment.

That Sugar Film is loaded with bittersweet facts, but nevertheless is digestible because of its humorous approach. Why did you decide to go this way with the film and how does it influence the outreach?

I actually came on board once the film was finished, so I can’t take any credit for the accessibility of Damon and Nick’s (the producer) approach to the topic. From an outreach perspective, their stylistic and tonal approach was an absolute gift, as while the film is disseminating confronting information for most audience members, you come away empowered to make better decisions about your eating habits rather than feeling confused, angry and bleak about the future.

You have already been able to develop a huge fan base for the film. What is the next step?

We’re currently working on a range of engagement activities for schools here in Australia. We’re developing partnerships to allow us to launch our School Action Toolkit and That Sugar App in other countries. Another big focus for us is developing more resources for a range of settings, like kindergartens, workplaces and hospitals. We’ll also be campaigning for clearer food labeling and better regulation of marketing practices (especially with regard to kids).

After watching documentaries, people often feel moved to learn more, take action or get involved in some way. Is there anything that you recommend to those who feel inspired by That Sugar Film?

Absolutely! First and foremost, we want people to share the film, book and our Website/Facebook page with their friends and families. We also encourage all parents to approach their kids school (via the Principal or parents committee) offering to help arrange a screening of the film for the whole school community (doing it as a fundraiser is a great option). If they encounter resistance, then another tip is to approach the teacher who teaches the ‘health’ curriculum (here in Australia, it’s the Health & Physical Education teacher) and ask them to consider using the film in the classroom. We have a free download of our Study Guide which can be accessed by signing up to the schools mailing list.

Community screenings are great too and we have a community screening kit available to help screening hosts plan and promote their event (the Discussion Guide created by Influence Film is a great resource too!).

What are your 6 favorite documentaries of all times?

Grey Gardens, One Day in September, Dark Days, Searching for Sugar Man, Capturing the Friedmans, The Gleaners and I – and That Sugar Film of course!

________________

THAT SUGAR FILM is Influence Film Club’s featured film for January. Each month Influence Film Club hand-picks one of our favorite docs as our club’s featured film to watch and discuss together. Throughout the month, starting with our newsletter and continuing on our website and social media we will extend the conversation by exploring the various issues touched on in the film, providing filmmaker interviews, suggesting ways to Influence, and discussing documentaries in general – because after all, We Love Docs.

Interview by: Julia Bier

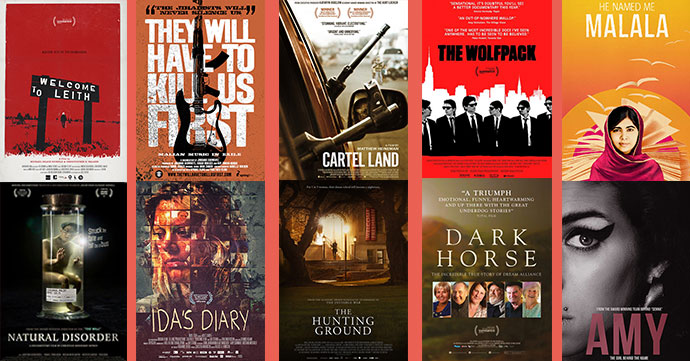

Documentaries from 2015 are daring to show us that its been another incredible year for film; more and more docs are focusing on characters – sometimes to tell the story of a greater cultural happening, and sometimes as a way to share with audiences a story that has never been told. Influence Film Club’s Top 10 Character Driven Documentaries from 2015 feature some extraordinary individuals, and these films go beyond the surface and invite us into the lives of others with unprecedented access. So go ahead, take a peek and lose yourself in the reality of our favorite character driven documentaries from 2015.

Welcome to Leith

Chronicling the alleged take-over of a small town in North Dakota by notorious white supremacist Craig Cobb, WELCOME TO LEITH examines a rural community’s struggle for sovereignty against an extremist vision.

They Will Have to Kill Us First

Music, one of the most important forms of communication and cultural connection in Mali, was banned in 2012 when Islamic extremist groups rose up to capture the northern section of the country. THEY WILL HAVE TO KILL US FIRST follows the influential musicians who give their all to surrender anything but their sound.

Cartel Land

With unprecedented access, CARTEL LAND is a riveting, on-the-ground look at the journeys of two modern-day vigilante groups on both sides of the U.S.-Mexican border, and their shared enemy – the murderous Mexican drug cartels.

The Wolfpack

THE WOLFPACK documents six bright teenage brothers have spent their entire lives locked away from society in a Manhattan housing project. All they know of the outside is gleaned from the movies they watch obsessively. Yet as adolescence looms, they dream of escape, ever more urgently, into the beckoning world.

He Named Me Malala

HE NAMED ME MALALA is an intimate portrait of Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Malala Yousafzai, who was targeted by the Taliban and severely wounded by a gunshot at the age of 15, and currently works as a leading campaigner for girls’ education globally as co founder of the Malala Fund.

Natural Disorder

Stand-up comedian Jacob Nossell, who was diagnosed with cerebral palsy as an infant, is on a quest to comprehend the concept of normality while challenging his own lack of skills. By staging a four-act play supplied with information from his family, scientists, philosophers, and actors, he attempts to figure out what the meaning of life is for him and others like him.

Ida’s Diary

A young Norwegian woman struggling with borderline personality disorder named Ida Storm chose a video diary as an outlet for her mood swings, a way to ease her mind and structure her thoughts. IDA’S DIARY invites the viewer into an anxiously intense insider’s view of a real life conducted under the auspices of mental illness.

The Hunting Ground

Following a group of victims gone activists as they defy shame and stigmatization to uncover the truth, THE HUNTING GROUND is a startling exposé of sexual assault on college campuses, their institutional cover-ups, and the devastating toll they take on students and their families.

Dark Horse

DARK HORSE is the inspirational true story of a group of friends from a former mining village in the Welsh countryside who decide to take on the elite “sport of kings” and breed themselves a racehorse.

Amy

A once-in-a-generation talent and a pure jazz artist in the most authentic sense, Amy wrote and sung from the heart using her musical gifts to analyze her own problems. Her huge success, however, resulted in relentless media attention which coupled with Amy’s troubled relationships and precarious lifestyle saw her life tragically begin to unravel.

Until 2014, Damon Gameau was primarily known for being an actor. Today, the Australian is known for far more than that – he is making us fundamentally rethink our food choices. As writer, producer, director and lead of our film of the month, THAT SUGAR FILM, he embarked on a journey to discover the sugary truth about foods marketed and commonly perceived as ‘healthy’. For two months, he would eat 40 teaspoons (160 grams) of sugar each day – the average amount a young, Australian male consumes. Yet, you won’t see him indulging in soft drinks and ice-cream but rather low-fat yoghurts and juice, groceries we consume in pursuit of a better health that hide their sugar-sweet-selfs behind the façade of do-gooders. Filmed as Damon was about to become a father, he decided it is about time to lift the veil on hidden sugar. So, for all of us victims numbed by sweet substances, let’s tune in and listen to his wake-up call.

What is it that draws you to documentary film?

George Orwell said, “In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” I actually think the world needs documentaries more than ever. They have become a wonderful form of modern journalism and can shine a light into our darkest corners.

That Sugar Film is your debut as a documentary director. What sparked your interest for becoming a human lab rat and at what point did you decide to make a film?

I was aware of the mixed messages around sugar in the public opinion. The camps were very divided so I wanted to find out some truths for myself. I always thought telling a story about sugar would also lend itself to some great aesthetics. A colorful Willy Wonka joyride.

You were the director while still having the lead role in the film. This is rather an exemption to the rule. Could you tell us a little about how you experienced it?

I certainly learnt a lot about myself doing it this way. My barometer is very finely tuned now for when I am truthful and when I am bullshitting. I have been an actor for 12 years so I am used to watching myself on screen and accepting the flaws. The tough part was eating all that sugar and trying to make smart decisions during the filming process.

The highlight of your film is that while everyone would expect you to have consumed sweet foods you actually switched to so-called healthy foods such as low-fat yogurt, cereals or fruit bars. So, what’s wrong with this “healthy” stuff?

There’s nothing ‘wrong’ with it, it’s just that people have been mislead into thinking it is all healthy. I think the point of the film is to try and teach people the true meaning of moderation. Most people think ice cream or chocolate is their only sugar for the day. Hopefully the film shows them exactly how much sugar they are consuming in other products.

One of the most impressive insights for me was how big of an influence sugar has on our mood and mentality. Are its effects comparable to those of a drug?

Well, Nora Volkow, the head of the National Institute of Drug Abuse in the US, acknowledges that sugar is a drug for some people and that is certainly the feedback we get. It all comes down to the size of the opioid receptors in your brain. [Opioid receptors are located in the brain and the spinal column. They are responsible for aiding neurotransmitters and hormones, the most well known being our endorphins. Addictive substances like Heroin work by enacting upon these receptor sites while high sugar foods can cause similar reactions.] Some are more prone to sugar addiction than others, in the same way alcohol and nicotine affects us all differently. Sugar is no different. The mood factor is a very important topic as I think most people are completely unaware of how sugar impacts their cognition.

Your film has created huge awareness for sugar and its effects on us – and the industry counting on us being sweet tooths. Now, how can people that watched your film take action and what are your hopes in terms of changing behaviors?

To take action, I would recommend people to check out our website where we provide lots of free recipes and tips. I also wrote a companion book to the film, That Sugar Book, that really walks you through the process of lowering sugar intake.

What people need to know is that their palate adjusts. Things might taste bland in the first few weeks of lowering sugar but then you begin to notice the natural sweetness of foods and that the refined stuff tastes way too strong.

Often after watching documentaries, people feel moved to take action or get involved in some way. What were and are you hoping for in terms of your film’s impact?

We have had an incredible outreach campaign that includes a free app, a school action kit that 1,000 schools have already signed up for and an Aboriginal Foundation for lowering sugar consumption on the lands. It is a full time job and tough to keep up with but we are thrilled with the response and support for all these ventures.

What would your playlist of documentary favorites consist of?

The Staircase, The Inside Job, The Bill Hicks Story, The Comedian, Man on Wire, Capturing the Friedmans, Bowling for Columbine, Searching for Sugar Man.

________________

THAT SUGAR FILM is Influence Film Club’s featured film for January. Each month Influence Film Club hand-picks one of our favorite docs as our club’s featured film to watch and discuss together. Throughout the month, starting with our newsletter and continuing on our website and social media we will extend the conversation by exploring the various issues touched on in the film, providing filmmaker interviews, suggesting ways to Influence, and discussing documentaries in general – because after all, We Love Docs.

Interview by: Julia Bier

The path he followed led him from snacking on leftovers at one of LA’s production houses to Chicago’s documentary powerhouse, Kartemquin. Would acclaimed editor and co-director of our December film, ALMOST THERE, Aaron Wickenden have thought he was going to have the career he has today when he was cracking the crust of crème brûlée in the mecca of film? It’s hard to know. But one thing is clear: not quite getting what you set out for, as the film’s title suggests, does not apply to Aaron. Amongst his several award winning collaborations are films like Oscar shortlisted Best of Enemies by Morgan Neville who described Aaron with the following words: “Docs, in general, are made in the edit bay, archival docs even more so… We brought in Aaron Wickenden, who cut Finding Vivian Maier, and he’s amazing.” See it for yourself!

What is it that draws you to documentary film?

The collaborative storytelling process is a big part of it… and with that, the joy that comes from working in small groups of passionate people. When I graduated from college in 2000 my work experience was the opposite to the career in documentary that I have now. I went to work at a major post production house in Los Angeles. I told the HR director I wanted to be an Assistant Editor. Instead I was assigned to the Client Services team where I would spend the next few months bringing espresso drinks and crème brûlées to advertising executives and show runners. After I mastered that, they promoted me to the Tape Vault where I put barcodes on film and tape elements and made sure they didn’t get lost in FedEx. It was a fun gig at first because I could zone out, eat crème brûlée leftovers and listen to KXLU while getting my work done. After a while it occurred to me that what I was doing had so little to do with the actual films and shows that we were working on that I might as well have been selling t-shirts. Nowadays, the teams I work on are usually about 3-5 people at the core: Director, Producer, Editor, and if I’m lucky an Associate Producer and Assistant Editor. The creative conversations I get to participate in at that level are fantastically stimulating.

You have worked as an editor on many films, including Finding Vivian Maier and The Interrupters. Can you tell us about your history with documentaries? In what way was it different from your previous experiences to work as a co-director on Almost There?

During college, one of my best and hippest friends turned me onto the radio show This American Life. It was early in that show’s history and I remember sitting in my friend’s loft in Tucson sparking off of all of these great stories and drinking lots of wine. Around that same time I stumbled across a copy of Kartemquin’s classic film Inquiring Nuns on VHS at my college’s library. That film blew my mind. Essentially the film is about two nuns walking around the streets of Chicago in 1968 asking people if they were happy. It features one of the first film scores by Phillip Glass who was a student at the University of Chicago. These experiences were among the first that sent me on my way towards docs.

In the winter of 2001, after moving to Chicago myself, I came across another copy of Inquiring Nuns at a great video store called Facets. I looked up Kartemquin online but at that time their website was really terrible and had no contact information. So I grabbed a phone book, found their listing and called to see if they had an internship program. The timing couldn’t have been better because Kartemquin was in the midst of creating a 7 hour mini-series for PBS called The New Americans and they needed all the help they could get. Another turning point in my career happened then because I met Steve James. He was incredibly kind, approachable, and sincere while also being very funny. He went on to hire me as his Assistant Editor on Reel Paradise which we premiered at Sundance in 2004. In a way, I was mentored by Steve over the years and he quickly promoted me up the post-production ladder to the point where we co-edited two films: At the Death House Door (2008), and The Interrupters (2011).

Only in the past few years I have started working with other directors and I’ve been very lucky to have some great filmmakers come my way. The resulting success of films like Finding Vivian Maier, The Trials of Muhammad Ali, and Best of Enemies only continues to help open my world up to new creative collaborations. Each experience is very different. The most different of which would be Almost There because I was co-directing and producing it with my talented friend Dan Rybicky. I was also the cinematographer, editor, and a minor character in the film. After completing Almost There I think I understand a bit better how exhausting it is to direct a documentary and push it out into the world. As a result I now have an expanded depth of compassion for my directors and the stresses they’re navigating.

You shot the film over the course of 8 years. How did you manage to keep control over the presumably extensive amount of footage? How do you find a starting point?

I’m pretty methodical and system oriented when it comes to my projects. However by contrast, my office is usually a mess and I wish I could declutter my living space with the same rigor that I do with my films. It’s one of my 5 year goals.

With Almost There we certainly had a mountain of footage that accumulated over the years. It was all organized by shoot date and then backed up onto multiple drives in case one of them failed. I still have eight external hard-dives hooked up next to my computer at home so that I can finish and deliver our TV version of the film which has to be about 56 minutes long. Believe me, I am looking forward to boxing up those drives and putting them into storage.

If we had just tried to attack the edit of the film by just diving in I think we would have failed miserably. We actually started by writing and submitting proposals to ITVS [Independent Television Service] as part of their Open Call process that can result in a TV acquisition. We applied 3 times before being successfully funded, and with each application our written description would get tighter and more refined. ITVS gave us feedback as we went along and it helped us understand how to tell our story. Once successfully funded we were faced with a new challenge: could we pull off what we had written in our proposal.

Though he certainly doesn’t appear as the easiest person to deal with, Peter Anton’s story is heart-wrenching and while watching the film you can’t help thinking how lucky he was to meet you and Dan. What does Almost There really mean to Peter and how is he doing today?

When we first met Peter he was living in a pretty horrible situation where his home was falling down around him and he had self-isolated from his community. Those were the conditions that compelled Peter to want to chronicle his life story. In writing about himself, I think he wanted to cultivate a certain kind of control and self-worth that he didn’t feel in his day-to-day life. He began making his scrapbooks in the early 1980s and by the time he was finished there would be 13 volumes comprising his life-story, Almost There. He explained to us that this title choice came from his life being composed of “almost there” experiences where he was close to succeeding but didn’t quite make it.

Now that Peter is out of his home, the film is out in the world, and he has reconnected with a community it’s clear that his compulsion to tell his life story has calmed down. He’s now working on other artistic pursuits: directing an elderly person’s choir, writing a massive book of facts about the world, and teaching art classes. He’s very fulfilled by these things.

The other day a very favorable review of our film came out in The Chicago Tribune. Peter read it and called me. He thought it was interesting but all he really wanted to do was to talk about how we were going to get his new book published. So he’s basically over the film… and that’s amazing.

Thinking of filmmaking as the art form it is, in what way has Peter’s story influenced your own pursuits as an artist?

My favorite art of Peter’s comes from a place of his compulsion. It’s work he has to make no matter what. As a freelance editor for hire, I try to chose to work with directors who feel that same need to make their film. I also try to judge how acutely I’m catching this contagious need for the film to be made. If I find myself wanting to tell my friends about a new project I’m working on and I can feel myself getting excited while I’m talking about the film, then those are good signs for its success. When those things aren’t in play, I’ve found that the purpose for the film existing in the world can get kind of diluted, the director can loose steam and the work becomes more of a job then a collaborative art. In those instances it’s still a wonderful job to have, and I’m lucky to be paid to be creative…but at the end of the day I’m in it for the process and want to be around people who are excited.

What has been the primary conversation you have observed people are having around the film? Has it stirred up some strong opinions?

When people watch the film it reminds them of conversations they’ve had with a family member or neighbor around moving out of their home and whether a nursing home is the right fit for them. While Peter is going though a pretty extreme version of this transition in our film, this pivotal time in a person’s life is very relatable. We’ve now shown the film at over 30 film festivals around the world and I’ve noticed people consistently leave the theater with a sense of expanded compassion towards the elderly. If that is the legacy of this film than I’m pretty happy with the outcome of this whole endeavor.

What are your 6 favorite documentaries of all times?

________________

ALMOST THERE is Influence Film Club’s featured film for December. Each month Influence Film Club hand-picks one of our favorite docs as our club’s featured film to watch and discuss together. Throughout the month, starting with our newsletter and continuing on our website and social media we will extend the conversation by exploring the various issues touched on in the film, providing filmmaker interviews, suggesting ways to Influence, and discussing documentaries in general – because after all, We Love Docs.

Interview by: Julia Bier

“The documentary form is one of the freest in cinema, while also being gloriously beholden to the ineffable weight of the real world and the delicate needs of real lives. This tension between limitless formal possibility and necessary moral constraint gives nonfiction a rare power…” – Robert Greene

People often forget that documentary is not a film genre, but the formal result of entrusting truth with enough structure to tell a story cinematically. Within non-fiction filmmaking there are documentaries that span the spectrum of genre, from war film (see Restrepo) to sports thriller (Hoop Dreams) through absurdist comedy (Gates of Heaven) and beyond, but when compared to these films’ fictional counterparts, there are a series of formal styles that documentaries most often embrace as the result of filmmaker intention and situational circumstance that are strictly inherent of the form, most notably the talking head, cinéma vérité and the archival compendium.

In academia these formal styles are broken down further into six types of cinematic non-fiction – poetic, expository, observational, participatory, reflexive and performative. While it’s true that some films may ride the line between the various types of documentaries, most can be categorized quite easily.

Poetic docs can be identified by their lack of characterial focus and narrative structure, often relying instead upon a lyrically associative form, impressionistic and essayistic. Godfrey Reggio’s monumental, environmentally minded KOYAANISQATSI is a perfect example. Riffing on the aesthetics of the traditional city symphony, the film comments on the impact of modernization on our planet through poetics rather than exposition. Its formal counterpoint then would be the expository smash hit MARCH OF THE PENGUINS, which documents the life of penguins with the god-like guidance of its narrator Morgan Freeman.

As one might expect, observational docs are typified by their hands off approach to filming their subjects, taking pains to remain non-interventional and typically remain free of any narrative commentary or the like. Philip Gröning’s INTO GREAT SILENCE is a wonderfully austere example of this style, simply documenting the routines of the devout monks who live within the Grande Chartreuse. The opposite of this approach might be exemplified by the participatory FINDING VIVIAN MAIER, in which John Maloof, the film’s co-director, places himself within the detective narrative of the posthumous discovery of the street photographer Vivian Maier. As in all participatory films, the filmmaker’s presence within the narrative is essential to the telling of the story.

Harder to discern is the reflexive and performative doc. While the Maysles brothers made a name for themselves as pioneers of direct cinema, their singular film GREY GARDENS reminds audiences to remember to question what they are seeing on screen. By drawing attention to the fact that what one is watching is in fact a film of questionable representation via performance and construction, they pushed the reflexive doc forward. Comparatively, Joshua Oppenheimer’s shocking depiction of the lingering cultural effects of the Indonesian killings of 1965–66, THE ACT OF KILLING is the quintessential performative doc. Pushing the limits of subjective experience by having his subjects, each former death-squad leaders, literally perform reenactments of their previous acts of murder, the film uses formal experimentation and personal accounts to simultaneously conjure visceral emotional responses while commenting on the horrific political situation that remains in Indonesia.

Though just a divisional taste of the forms that documentary films may take, these six films give you a glimpse of academia. As you take in more non-fiction films, try to discern which of these categories films fit in – poetic, expository, observational, participatory, reflexive or performative?

Koyaanisqatsi

Created between 1975 and 1982, KOYAANISQATSI (“life out of balance”) is an apocalyptic vision of the collision of two different worlds — urban life and technology versus the environment – complete with musical score by Philip Glass.

March of the Penguins

MARCH OF THE PENGUINS documents the emperor penguins annual journey taking them hundreds of miles across the brutal Antarctic landscape through the harshest weather conditions on earth – risking starvation and attack by dangerous predators in the quest for love and life.

Into Great Silence

INTO GREAT SILENCE is an intimate portrayal and examination of the life of the devout monks who live within the Grande Chartreuse, the head monastery of the reclusive Carthusian Order situated in the French Alps.

Finding Vivian Maier

The discovery of over 100,000 photographs hidden away in various storage lockers unveiled the story of Vivian Maier, a mysterious nanny, who is now considered one of the 20th century’s greatest street photographers.

Grey Gardens

In GREY GARDENS we meet Big and Little Edie Beale—mother and daughter, high-society dropouts, reclusive cousins of Jackie O.—thriving together amid the decay and disorder of their ramshackle East Hampton mansion.

The Act of Killing

THE ACT OF KILLING follows former Indonesian death squad leaders as they are challenged to re-enact the real-life mass killings in the cinematic genres of their choice, from classic Hollywood crime scenarios to lavish musical numbers.

While making ALMOST THERE was a life-altering experience for co-director Dan Rybicky, our team’s first encounter with the Chicago based filmmaker could very well be described with the same term. Seldom have I seen a similar expression of joy and gratitude as when first meeting and shaking hands with Dan at this year’s Sheffield Doc/Fest. Hence, I am happy that we have the opportunity to feature ALMOST THERE, a documentary brought to us by a brilliant, congenial team of filmmakers who try to brighten the future of an amazing artist buried in the past. ALMOST THERE might be Dan’s first full-length feature but he is no stranger to the film industry. With an MFA from New York’s Tisch School of Arts under his belt, he got involved in various production capacities for filmmakers like Martin Scorsese, John Sayles and John Leguizamo. In his current position as Associate Professor in Cinema Art + Science at Columbia College Chicago he is at least as cherished by his students as he was by me throughout the interview, so let’s have a closer look at the first of the two creative minds behind our December doc.

What is it that draws you to documentary film?

I love how passionate, purposeful and humane documentary films and filmmakers are, and I’m challenged in a wonderful way by the inherent tensions and complexities contained within John Grierson’s early definition of documentary as “the creative treatment of actuality.” Best of all, I’m grateful for the discoveries I’ve made and lessons I’ve learned during the process of shining a literal and metaphorical light on the always fascinating, unpredictable, and inspiring lives of the real people I’ve met – and those I look forward to meeting soon.

What is your history? Is there a red thread that has followed you throughout your career as a documentary filmmaker and in other pursuits?

For better or worse, I’m a person who has always picked the scab and scratched the itch, even when I was told not to. As a kid, my family called me “the shit disturber” because I spoke out about the lies and injustices I saw to those close to me who preferred, and even demanded, silence. I’m sure I was really annoying (and probably still am), but this early quest for truth (which has evolved into more of a meditation on what truth is and isn’t) – combined with my endless curiosity about people and why and how their stories are told – first led me to pursuing a career as a playwright and screenwriter. And while I do still enjoy putting my words into other people’s mouths, I’ve become increasingly more interested in listening to non-actors speak their own words and seeing how the narrative structures and character arcs I’ve employed in my fiction apply – or don’t – to the complicated lives and surprising stories of real people. Ultimately, it is my deep love for these real (and really great) characters – especially those who are at a turning point in their lives and deeply desire something – that has made me become a documentary filmmaker.

So, you came across Peter Anton at a Pierogi Festival – probably one of the most fun stories a filmmaker can tell about how they found inspiration for a new project. What sparked your interest? At what point did you decide to start working on Almost There?

It’s true that my friend and co-director Aaron Wickenden and I first met Peter Anton during the summer of 2006 at Pierogi Fest in Northwest Indiana, having initially gone there because the festival was trying to get into the Guinness Book of World Records by unveiling “The World’s Largest Pierogi.” We brought our cameras with us because we thought that buttery mountain of dough would be a sight to behold. Little did we know we would encounter someone who would change the course of our lives for the next decade.

Peter was sitting at a rickety table off of the main festival path dressed like a disheveled dandy persuading passersby to let him draw their portraits. We were charmed by his corny jokes and mesmerized by how much the kids he was drawing loved him. And then from under his table, Peter pulled out one of his twelve gigantic and totally handmade scrapbooks. It vibrated with color, glitter and text, and we were immediately drawn in.

We wrote letters back and forth for two years before finally visiting Peter at his house in 2008 so he could show us more of his art. When we got there, we were deeply saddened yet intrigued to learn that Peter was a hoarder living in extreme squalor, surrounded by artistic gems buried in rubble and mold. We were excited to discover this body of artwork but majorly concerned for Peter’s well being. What shocked us the most was how determined Peter was to stay living in such life-threatening conditions. After offering Peter information about social service organizations that could help him secure better housing, we were finally forced to accept Peter’s wishes. But because we remained interested in this tension between the past and present that exists in Peter’s art and life, we began documenting him, his house, and his art before everything was damaged beyond recognition.

Almost There is a very personal film, focusing not only on Peter but also on you as you become a subject of the documentary and share your personal history. When did you realize that you would become a part of the story, and what was that experience like for you?

Aaron and I did not begin this film wanting or expecting to become supporting characters in it, but while reviewing our footage, we realized some of the most dramatic exchanges that brought the deepest conflicts of Peter’s life and story immediately to the surface were between him and us. This is not so surprising in retrospect, considering Peter lived in almost total isolation and we were two of the only people he would see or talk to for weeks at a time.

But only during our fourth year of our collaboration was I able to more deeply explore my own motivation for telling Peter’s story when, soon after the art exhibition in Chicago we had helped Peter set up, a journalist discovered a disturbing secret from Peter’s past – something he had kept from us. My friends saw how upset Aaron and I were about it and started to ask me why I was still documenting this man’s life now that he’d lied to us. Why did I feel the need to continue helping Peter so much even though he actively refused to help himself?

During a visit to my hometown, I began to look more closely at the parallels between Peter’s story and the story of my family and quickly realized how much my desire to help Peter in the present was related to my not being able to help my own mentally ill brother in the past – a brother who, like Peter years ago, was an artist still living in the house he grew up in with his (and my) mother.

I’ve always been wary of the ‘God-eye’ in documentary anyway and often wish more directors revealed on screen the ethically complicated and hard-to-define relationships that have developed between them and their subjects over the course of filming. Although this is usually the stuff they edit out, these “behind-the-scenes” negotiations and power dynamics contain stories I find as interesting, if not more interesting, than the ones the directors have chosen to tell. Based on this, and based on my determination to hold myself up to the same scrutiny I give to a subject, Aaron and I decided that developing my character and showing my motivations would add an additional layer of depth and context to our story and pull the veil back even further on the process of documentary making itself.

Comparing his situation to van Gogh’s Peter says: “Only the art matters, not the mess.” Having been a regular at Peter’s, what is your opinion?

As Victor E. Frankel wrote in one of my favorite books Man’s Search for Meaning, “Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how’.” Peter definitely confirmed my belief in the truthfulness of something because it was only through his passion for art making – combined with the deeper sense of purposefulness he derived from creating work based on the story of his life and those in his community – that he was able to survive and even thrive in conditions I’m sure would have killed anybody else.

Based on this, I would agree with Peter that art does definitely matter more than the mess. That said, and considering how much the mess threatened to destroy both Peter’s life and his art, I think both are important.

Often after watching documentaries, people feel moved to take action or get involved in some way. What were and are you hoping for in terms of your film’s impact?

I didn’t think about what impact I wanted our film to have while we were making it. All I wanted during that time was for Peter to not die alone with all of his art buried in the decrepit house he was “living” in. Only upon completing the film have I been able to see the impact it has on others – not just on various art communities but also on anyone who is confronting issues involving poverty, the elderly, the disabled, and those with mental illness. Peter’s story may be extreme, but it is ultimately universal: most everyone has a friend, relative or neighbor who mirrors some of Peter’s eccentricities, and sooner or later, everyone copes with end-of-life issues with a parent or grandparent. And we can all relate to the difficulty of letting go, as well as the fear of making long-term changes, even when those changes may be for the better.