The path he followed led him from snacking on leftovers at one of LA’s production houses to Chicago’s documentary powerhouse, Kartemquin. Would acclaimed editor and co-director of our December film, ALMOST THERE, Aaron Wickenden have thought he was going to have the career he has today when he was cracking the crust of crème brûlée in the mecca of film? It’s hard to know. But one thing is clear: not quite getting what you set out for, as the film’s title suggests, does not apply to Aaron. Amongst his several award winning collaborations are films like Oscar shortlisted Best of Enemies by Morgan Neville who described Aaron with the following words: “Docs, in general, are made in the edit bay, archival docs even more so… We brought in Aaron Wickenden, who cut Finding Vivian Maier, and he’s amazing.” See it for yourself!

What is it that draws you to documentary film?

The collaborative storytelling process is a big part of it… and with that, the joy that comes from working in small groups of passionate people. When I graduated from college in 2000 my work experience was the opposite to the career in documentary that I have now. I went to work at a major post production house in Los Angeles. I told the HR director I wanted to be an Assistant Editor. Instead I was assigned to the Client Services team where I would spend the next few months bringing espresso drinks and crème brûlées to advertising executives and show runners. After I mastered that, they promoted me to the Tape Vault where I put barcodes on film and tape elements and made sure they didn’t get lost in FedEx. It was a fun gig at first because I could zone out, eat crème brûlée leftovers and listen to KXLU while getting my work done. After a while it occurred to me that what I was doing had so little to do with the actual films and shows that we were working on that I might as well have been selling t-shirts. Nowadays, the teams I work on are usually about 3-5 people at the core: Director, Producer, Editor, and if I’m lucky an Associate Producer and Assistant Editor. The creative conversations I get to participate in at that level are fantastically stimulating.

You have worked as an editor on many films, including Finding Vivian Maier and The Interrupters. Can you tell us about your history with documentaries? In what way was it different from your previous experiences to work as a co-director on Almost There?

During college, one of my best and hippest friends turned me onto the radio show This American Life. It was early in that show’s history and I remember sitting in my friend’s loft in Tucson sparking off of all of these great stories and drinking lots of wine. Around that same time I stumbled across a copy of Kartemquin’s classic film Inquiring Nuns on VHS at my college’s library. That film blew my mind. Essentially the film is about two nuns walking around the streets of Chicago in 1968 asking people if they were happy. It features one of the first film scores by Phillip Glass who was a student at the University of Chicago. These experiences were among the first that sent me on my way towards docs.

In the winter of 2001, after moving to Chicago myself, I came across another copy of Inquiring Nuns at a great video store called Facets. I looked up Kartemquin online but at that time their website was really terrible and had no contact information. So I grabbed a phone book, found their listing and called to see if they had an internship program. The timing couldn’t have been better because Kartemquin was in the midst of creating a 7 hour mini-series for PBS called The New Americans and they needed all the help they could get. Another turning point in my career happened then because I met Steve James. He was incredibly kind, approachable, and sincere while also being very funny. He went on to hire me as his Assistant Editor on Reel Paradise which we premiered at Sundance in 2004. In a way, I was mentored by Steve over the years and he quickly promoted me up the post-production ladder to the point where we co-edited two films: At the Death House Door (2008), and The Interrupters (2011).

Only in the past few years I have started working with other directors and I’ve been very lucky to have some great filmmakers come my way. The resulting success of films like Finding Vivian Maier, The Trials of Muhammad Ali, and Best of Enemies only continues to help open my world up to new creative collaborations. Each experience is very different. The most different of which would be Almost There because I was co-directing and producing it with my talented friend Dan Rybicky. I was also the cinematographer, editor, and a minor character in the film. After completing Almost There I think I understand a bit better how exhausting it is to direct a documentary and push it out into the world. As a result I now have an expanded depth of compassion for my directors and the stresses they’re navigating.

You shot the film over the course of 8 years. How did you manage to keep control over the presumably extensive amount of footage? How do you find a starting point?

I’m pretty methodical and system oriented when it comes to my projects. However by contrast, my office is usually a mess and I wish I could declutter my living space with the same rigor that I do with my films. It’s one of my 5 year goals.

With Almost There we certainly had a mountain of footage that accumulated over the years. It was all organized by shoot date and then backed up onto multiple drives in case one of them failed. I still have eight external hard-dives hooked up next to my computer at home so that I can finish and deliver our TV version of the film which has to be about 56 minutes long. Believe me, I am looking forward to boxing up those drives and putting them into storage.

If we had just tried to attack the edit of the film by just diving in I think we would have failed miserably. We actually started by writing and submitting proposals to ITVS [Independent Television Service] as part of their Open Call process that can result in a TV acquisition. We applied 3 times before being successfully funded, and with each application our written description would get tighter and more refined. ITVS gave us feedback as we went along and it helped us understand how to tell our story. Once successfully funded we were faced with a new challenge: could we pull off what we had written in our proposal.

Though he certainly doesn’t appear as the easiest person to deal with, Peter Anton’s story is heart-wrenching and while watching the film you can’t help thinking how lucky he was to meet you and Dan. What does Almost There really mean to Peter and how is he doing today?

When we first met Peter he was living in a pretty horrible situation where his home was falling down around him and he had self-isolated from his community. Those were the conditions that compelled Peter to want to chronicle his life story. In writing about himself, I think he wanted to cultivate a certain kind of control and self-worth that he didn’t feel in his day-to-day life. He began making his scrapbooks in the early 1980s and by the time he was finished there would be 13 volumes comprising his life-story, Almost There. He explained to us that this title choice came from his life being composed of “almost there” experiences where he was close to succeeding but didn’t quite make it.

Now that Peter is out of his home, the film is out in the world, and he has reconnected with a community it’s clear that his compulsion to tell his life story has calmed down. He’s now working on other artistic pursuits: directing an elderly person’s choir, writing a massive book of facts about the world, and teaching art classes. He’s very fulfilled by these things.

The other day a very favorable review of our film came out in The Chicago Tribune. Peter read it and called me. He thought it was interesting but all he really wanted to do was to talk about how we were going to get his new book published. So he’s basically over the film… and that’s amazing.

Thinking of filmmaking as the art form it is, in what way has Peter’s story influenced your own pursuits as an artist?

My favorite art of Peter’s comes from a place of his compulsion. It’s work he has to make no matter what. As a freelance editor for hire, I try to chose to work with directors who feel that same need to make their film. I also try to judge how acutely I’m catching this contagious need for the film to be made. If I find myself wanting to tell my friends about a new project I’m working on and I can feel myself getting excited while I’m talking about the film, then those are good signs for its success. When those things aren’t in play, I’ve found that the purpose for the film existing in the world can get kind of diluted, the director can loose steam and the work becomes more of a job then a collaborative art. In those instances it’s still a wonderful job to have, and I’m lucky to be paid to be creative…but at the end of the day I’m in it for the process and want to be around people who are excited.

What has been the primary conversation you have observed people are having around the film? Has it stirred up some strong opinions?

When people watch the film it reminds them of conversations they’ve had with a family member or neighbor around moving out of their home and whether a nursing home is the right fit for them. While Peter is going though a pretty extreme version of this transition in our film, this pivotal time in a person’s life is very relatable. We’ve now shown the film at over 30 film festivals around the world and I’ve noticed people consistently leave the theater with a sense of expanded compassion towards the elderly. If that is the legacy of this film than I’m pretty happy with the outcome of this whole endeavor.

What are your 6 favorite documentaries of all times?

________________

ALMOST THERE is Influence Film Club’s featured film for December. Each month Influence Film Club hand-picks one of our favorite docs as our club’s featured film to watch and discuss together. Throughout the month, starting with our newsletter and continuing on our website and social media we will extend the conversation by exploring the various issues touched on in the film, providing filmmaker interviews, suggesting ways to Influence, and discussing documentaries in general – because after all, We Love Docs.

Interview by: Julia Bier

While making ALMOST THERE was a life-altering experience for co-director Dan Rybicky, our team’s first encounter with the Chicago based filmmaker could very well be described with the same term. Seldom have I seen a similar expression of joy and gratitude as when first meeting and shaking hands with Dan at this year’s Sheffield Doc/Fest. Hence, I am happy that we have the opportunity to feature ALMOST THERE, a documentary brought to us by a brilliant, congenial team of filmmakers who try to brighten the future of an amazing artist buried in the past. ALMOST THERE might be Dan’s first full-length feature but he is no stranger to the film industry. With an MFA from New York’s Tisch School of Arts under his belt, he got involved in various production capacities for filmmakers like Martin Scorsese, John Sayles and John Leguizamo. In his current position as Associate Professor in Cinema Art + Science at Columbia College Chicago he is at least as cherished by his students as he was by me throughout the interview, so let’s have a closer look at the first of the two creative minds behind our December doc.

What is it that draws you to documentary film?

I love how passionate, purposeful and humane documentary films and filmmakers are, and I’m challenged in a wonderful way by the inherent tensions and complexities contained within John Grierson’s early definition of documentary as “the creative treatment of actuality.” Best of all, I’m grateful for the discoveries I’ve made and lessons I’ve learned during the process of shining a literal and metaphorical light on the always fascinating, unpredictable, and inspiring lives of the real people I’ve met – and those I look forward to meeting soon.

What is your history? Is there a red thread that has followed you throughout your career as a documentary filmmaker and in other pursuits?

For better or worse, I’m a person who has always picked the scab and scratched the itch, even when I was told not to. As a kid, my family called me “the shit disturber” because I spoke out about the lies and injustices I saw to those close to me who preferred, and even demanded, silence. I’m sure I was really annoying (and probably still am), but this early quest for truth (which has evolved into more of a meditation on what truth is and isn’t) – combined with my endless curiosity about people and why and how their stories are told – first led me to pursuing a career as a playwright and screenwriter. And while I do still enjoy putting my words into other people’s mouths, I’ve become increasingly more interested in listening to non-actors speak their own words and seeing how the narrative structures and character arcs I’ve employed in my fiction apply – or don’t – to the complicated lives and surprising stories of real people. Ultimately, it is my deep love for these real (and really great) characters – especially those who are at a turning point in their lives and deeply desire something – that has made me become a documentary filmmaker.

So, you came across Peter Anton at a Pierogi Festival – probably one of the most fun stories a filmmaker can tell about how they found inspiration for a new project. What sparked your interest? At what point did you decide to start working on Almost There?

It’s true that my friend and co-director Aaron Wickenden and I first met Peter Anton during the summer of 2006 at Pierogi Fest in Northwest Indiana, having initially gone there because the festival was trying to get into the Guinness Book of World Records by unveiling “The World’s Largest Pierogi.” We brought our cameras with us because we thought that buttery mountain of dough would be a sight to behold. Little did we know we would encounter someone who would change the course of our lives for the next decade.

Peter was sitting at a rickety table off of the main festival path dressed like a disheveled dandy persuading passersby to let him draw their portraits. We were charmed by his corny jokes and mesmerized by how much the kids he was drawing loved him. And then from under his table, Peter pulled out one of his twelve gigantic and totally handmade scrapbooks. It vibrated with color, glitter and text, and we were immediately drawn in.

We wrote letters back and forth for two years before finally visiting Peter at his house in 2008 so he could show us more of his art. When we got there, we were deeply saddened yet intrigued to learn that Peter was a hoarder living in extreme squalor, surrounded by artistic gems buried in rubble and mold. We were excited to discover this body of artwork but majorly concerned for Peter’s well being. What shocked us the most was how determined Peter was to stay living in such life-threatening conditions. After offering Peter information about social service organizations that could help him secure better housing, we were finally forced to accept Peter’s wishes. But because we remained interested in this tension between the past and present that exists in Peter’s art and life, we began documenting him, his house, and his art before everything was damaged beyond recognition.

Almost There is a very personal film, focusing not only on Peter but also on you as you become a subject of the documentary and share your personal history. When did you realize that you would become a part of the story, and what was that experience like for you?

Aaron and I did not begin this film wanting or expecting to become supporting characters in it, but while reviewing our footage, we realized some of the most dramatic exchanges that brought the deepest conflicts of Peter’s life and story immediately to the surface were between him and us. This is not so surprising in retrospect, considering Peter lived in almost total isolation and we were two of the only people he would see or talk to for weeks at a time.

But only during our fourth year of our collaboration was I able to more deeply explore my own motivation for telling Peter’s story when, soon after the art exhibition in Chicago we had helped Peter set up, a journalist discovered a disturbing secret from Peter’s past – something he had kept from us. My friends saw how upset Aaron and I were about it and started to ask me why I was still documenting this man’s life now that he’d lied to us. Why did I feel the need to continue helping Peter so much even though he actively refused to help himself?

During a visit to my hometown, I began to look more closely at the parallels between Peter’s story and the story of my family and quickly realized how much my desire to help Peter in the present was related to my not being able to help my own mentally ill brother in the past – a brother who, like Peter years ago, was an artist still living in the house he grew up in with his (and my) mother.

I’ve always been wary of the ‘God-eye’ in documentary anyway and often wish more directors revealed on screen the ethically complicated and hard-to-define relationships that have developed between them and their subjects over the course of filming. Although this is usually the stuff they edit out, these “behind-the-scenes” negotiations and power dynamics contain stories I find as interesting, if not more interesting, than the ones the directors have chosen to tell. Based on this, and based on my determination to hold myself up to the same scrutiny I give to a subject, Aaron and I decided that developing my character and showing my motivations would add an additional layer of depth and context to our story and pull the veil back even further on the process of documentary making itself.

Comparing his situation to van Gogh’s Peter says: “Only the art matters, not the mess.” Having been a regular at Peter’s, what is your opinion?

As Victor E. Frankel wrote in one of my favorite books Man’s Search for Meaning, “Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how’.” Peter definitely confirmed my belief in the truthfulness of something because it was only through his passion for art making – combined with the deeper sense of purposefulness he derived from creating work based on the story of his life and those in his community – that he was able to survive and even thrive in conditions I’m sure would have killed anybody else.

Based on this, I would agree with Peter that art does definitely matter more than the mess. That said, and considering how much the mess threatened to destroy both Peter’s life and his art, I think both are important.

Often after watching documentaries, people feel moved to take action or get involved in some way. What were and are you hoping for in terms of your film’s impact?

I didn’t think about what impact I wanted our film to have while we were making it. All I wanted during that time was for Peter to not die alone with all of his art buried in the decrepit house he was “living” in. Only upon completing the film have I been able to see the impact it has on others – not just on various art communities but also on anyone who is confronting issues involving poverty, the elderly, the disabled, and those with mental illness. Peter’s story may be extreme, but it is ultimately universal: most everyone has a friend, relative or neighbor who mirrors some of Peter’s eccentricities, and sooner or later, everyone copes with end-of-life issues with a parent or grandparent. And we can all relate to the difficulty of letting go, as well as the fear of making long-term changes, even when those changes may be for the better.

While our film also explores the how’s and why’s of compassion, as well as the limits of altruism, it more specifically provides a portrait of what aging is like for many people in America who have no family members left and currently live at or below the poverty level. Several people have approached us after screenings to tell us how much they hope every elderly person – and every person taking care of someone who is elderly – will see what we’ve made.

What would your playlist of documentary favorites consist of?

My list of doc favorites would be way too long to share in its entirety here, so I’ll instead highlight some of my favorites that were particular inspirations during the making of Almost There. Three are from our amazing production collective Kartemquin Films: Stevie, Home For Life, and Golub: Late Works are the Catastrophes. Other fantastic films I thought about a lot while making our film include: Grey Gardens, Marwencol, Crumb, American Movie, Little Dieter Needs to Fly, Mr. Dial Has Something to Say, and last but not least, The Devil and Daniel Johnston.

________________

ALMOST THERE is Influence Film Club’s featured film for December. Each month Influence Film Club hand-picks one of our favorite docs as our club’s featured film to watch and discuss together. Throughout the month, starting with our newsletter and continuing on our website and social media we will extend the conversation by exploring the various issues touched on in the film, providing filmmaker interviews, suggesting ways to Influence, and discussing documentaries in general – because after all, We Love Docs.

Interview by: Julia Bier

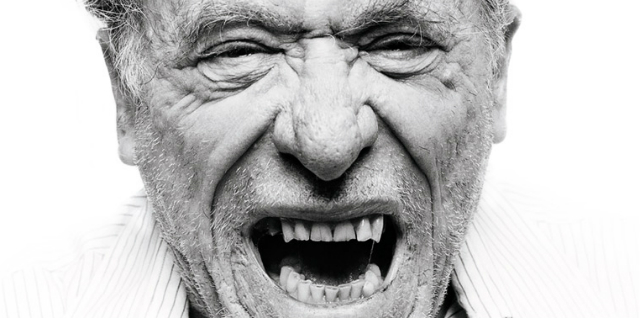

“You’ve got to burn straight up and down and then maybe sideways for a while and have your guts scrambled by a bully and the demonic ladies, you’ve got to run along the edge of madness teetering, you’ve got to starve like a winter alleycat, you’ve go to live with the imbecility of at least a dozen cities, then maybe maybe maybe you might know where you are for a tiny blinking moment.” – Charles Bukowski

Much like Bukowski himself, who spent much of his 73 years in the crazed haze of an alcohol infused fervor, enduring the whoas and joys of a starving artist with the emotional and creative extremes that come with such a provocative lifestyle, artists throughout history have often embraced all forms of madness in hopes of harnessing wild eyed authenticity in the name of art and purpose. For many, suffering and beauty are two sides of the same coin.

Non-fiction cinema is packed to the gills with such characters, from the men and women behind the cameras to those who’ve submitted themselves freely to be taken in by our watchful gaze. Like the wildly empathetic, grizzly obsessed nature-boy whom lost his life to the jaws of those he so loved in GRIZZLY MAN, the manic-depressive emotionally raw singer/songwriter at the heart of THE DEVIL AND DANIEL JOHNSTON, or the OCD-afflicted world travelling freedom fighter of POINT AND SHOOT, many are propelled to document their own unstable existences, unknowingly reaching out on their own to the anonymous unknown as if the visual documentation of one’s life itself might bring some form of lucidity to an otherwise mad caper. As we see, autobiography doesn’t seem to make their journey through life any easier, yet they continue nonetheless.

Others merely embrace their lunacy, knowing all along that their life’s endeavors are those of idealistic moonstruck dreams. The tightrope walker of MAN ON WIRE damns all logic, personal safety, and even legality in an act of singularly spectacular physical performance, while the abiding filmmaker of AMERICAN MOVIE, eyes deep in debt and personal crises, obsessively crusades in the name of his perfect picture. And much like Bukowski himself, the starving outsider artist at the center of ALMOST THERE has lived a life fueled and haunted by mental volatility in the pursuit of artistic revelation. Sometimes one must let go of reason and stability to reach out for something greater.

The following six films bring us closer to that “edge of madness” that Bukowski so lovingly speaks of, allowing us a view of the world detached from logic through the eyes of dreamers and madmen.

Man on Wire

MAN ON WIRE explores tightrope walker Philippe Petit’s daring, but illegal, high-wire routine performed between the twin towers of New York City’s World Trade Center in what some consider “the artistic crime of the century”.

Grizzly Man

In GRIZZLY MAN Werner Herzog explores the life and death of Timothy Treadwell who lived among the grizzly bears of Alaska for 13 consecutive summers until being attacked and eaten by a bear in 2003.

Almost There

For filmmakers Rybicky and Wickenden, Peter Anton’s home is a treasure trove, a startling collection of unseen and fascinating paintings, drawings, and notebooks, not to mention Anton himself. ALMOST THERE is a remarkable journey following a gifted artist through startling twists and turns.

American Movie

The story of filmmaker Mark Borchardt, his mission, and his dream. Spanning over two years of intense struggle with making a movie, family issues, financial decline, and personal crisis, AMERICAN MOVIE is a portrait of ambition, obsession, excess, and one man’s formidable quest for the American Dream.

Point and Shoot

With a gun in one hand and a camera in the other, 28-year-old OCD-afflicted Matthew VanDyke set off on a 35,000-mile motorcycle trip through Northern Africa and the Middle East, where he undergoes a self-described “crash-course in manhood.”

The Devil and Daniel Johnston

THE DEVIL AND DANIEL JOHNSTON follows the long and winding road traversed by Daniel Johnston – manic-depressive singer/songwriter/artist – on his way from childhood to manhood in this portrait of madness, creativity and unrequited love.

Thank you everyone for an incredible festival!

What a joy to meet with such an engaged audience and the incredibly talented filmmakers below.

Film pages will be coming soon for all of the films we discussed at the club.

Thank you:

Director Jerry Rothwell of “How to Change the World”, Directors Aaron Wickenden and Dan Rybicky of “Almost There” and Tim Horsburgh, Director of Communications and Distribution at Kartemquin Films, Director Leslee Udwin of “India’s Daughter”. Director Laura Nix of “The Yes Men are Revolting”, Director Kirby Dick of “The Hunting Ground”, Director Louise Osmond of “Dark Horse”, and of course The Sheffield Doc/Fest Crew

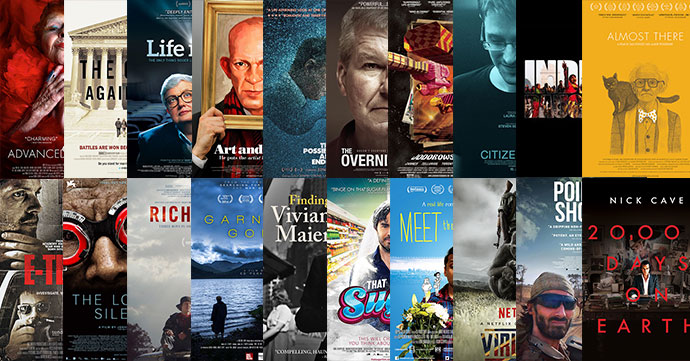

What can we say? 2014 was a cornerstone year for docs. Now, more than ever, we can cry out that “documentary is not a genre” and work to redefine the boring, dry, talking heads comes to mind when a friend suggests watching a documentary together. Documentaries can be thrillers, dramas, comedies, romance, adventures, and feel-good films. And Influence Film Club’s 20 Character Driven Documentary Favorites are a testament to that. Narrowing this list down to 20 was no easy task, but after weeks of debate we carved out a list of this year’s documentary favorites.

Advanced Style

Based on Ari Seth Cohen’s blog, ADVANCED STYLE paints intimate and colorful portraits of seven independent, stylish New York women aged 62 to 95 who are challenging conventional ideas about beauty, aging, and Western’s culture’s increasing obsession with youth.

The Case Against 8

THE CASE AGAINST 8 offers a behind-the-scenes look inside the historic case to overturn California’s ban on same-sex marriage. The film follows the unlikely legal team and the two same-sex couples who act as plaintiffs in the story of how they took the first federal marriage equality lawsuit to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Life Itself

LIFE ITSELF explores Roger Ebert’s legacy, including his Pulitzer Prize-winning film criticism at the Chicago Sun-Times and his eruptive relationship with Gene Siskel, all culminating in his ascension as one of the most influential cultural voices in America.

Art and Craft

Beginning as a cat-and-mouse art caper concerning one of the most prolific art forgers in U.S. history, ART AND CRAFT is rooted in questions of authorship and authenticity, eventually giving way to an intimate story of mental health and the universal need for community, appreciation, and purpose.

The Possibilities are Endless

After experiencing a stroke, Edwyn Collins could only say two phrases: ‘Grace Maxwell’ and ‘The Possibilities Are Endless’. Placed inside Edwyn’s mind, we embark on a journey from the brink of death back to language, music, and love on an intimate tale of rediscovery.

The Overnighters

THE OVERNIGHTERS is the story of the broken, desperate men chasing their dreams and running from their demons in the North Dakota oil fields and the local Pastor who risks everything to help them.

Jodorowsky’s Dune

Exploring the genesis of one of cinema’s greatest epics that never was – cult filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky’s adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune – this inspirational story about the power of the creative spirit establishes Jodorowsky as a master of cinema and a true visionary.

Citizenfour

CITIZENFOUR gives audiences unprecedented access to filmmaker Laura Poitras and journalist Glenn Greenwald’s encounters with Edward Snowden as he hands over classified documents providing evidence of mass indiscriminate and illegal invasions of privacy by the National Security Agency.

India’s Daughter

INDIA’S DAUGHTER depicts the investigation of the brutal gang rape and murder of a 23-year-old female medical student on a moving bus in Delhi, India, in December 2012.

Almost There

For filmmakers Rybicky and Wickenden, Peter Anton’s home is a treasure trove, a startling collection of unseen and fascinating paintings, drawings, and notebooks, not to mention Anton himself. ALMOST THERE is a remarkable journey following a gifted artist through startling twists and turns.

E-Team

Anna, Ole, Fred and Peter are four members of the Emergencies Team, the most intrepid division of the respected, international Human Rights Watch organization. E-TEAM is the personal, intimate story of how they lead their lives as they set out to shine light in dark places and give voice to thousands whose stories would never otherwise have been told.

The Look of Silence

Through its footage of perpetrators of the 1965 Indonesian genocide in THE ACT OF KILLING, a family of survivors discovers how their son was murdered and the identities of the killers. THE LOOK OF SILENCE serves as a powerful companion piece that initiates and bears witness to the collapse of fifty years of silence.

Rich Hill

Directors Andrew Droz Palermo and Tracy Droz Tragos, cousins with family connections to the community of RICH HILL, return to chronicle the lives of three boys in an examination of the challenges, hopes and dreams of the residents in rural Missouri.

Garnet’s Gold

GARNET’S GOLD follows one extraordinary man’s quixotic adventure in search of hidden treasure, in a belated rite of passage to rediscover the meaning of his life.

Finding Vivian Maier

The discovery of over 100,000 photographs hidden away in various storage lockers unveiled the story of Vivian Maier, a mysterious nanny, who is now considered one of the 20thcentury’s greatest street photographers.

That Sugar Film

Follow director Damon Gameau as he embarks on a unique experiment to document the effects of a high sugar diet on a healthy body, consuming only foods that are commonly perceived as ‘healthy’. THAT SUGAR FILM will forever change the way you think about the foods you eat and the hidden sugars lurking nearly everywhere.

Meet the Patels

Filmed by Geeta V. Patel, the sister of Ravi – an almost-30-year-old Indian-American who enters a love triangle between the woman of his dreams and his parents –in what started as a family vacation video, MEET THE PATELS is a hilarious and heartbreaking film about how love is truly a family affair.

Virunga

VIRUNGA is a gripping exposé of the realities of life in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the incredible true story of a group of brave people risking their lives to build a better future in a part of Africa the world has forgotten.

Point and Shoot

With a gun in one hand and a camera in the other, 28-year-old OCD-afflicted Matthew VanDyke set off on a 35,000-mile motorcycle trip through Northern Africa and the Middle East, where he undergoes a self-described “crash-course in manhood.”

20.000 Days on Earth

Delving into Nick Cave’s artistic processes, 20,000 DAYS ON EARTH takes us deep into the heart of how myth, memory, love and loss shape our lives, every single day. Fusing drama and documentary this film is a beautiful ode to the artistic process and an intimate portrayal of one musician’s creative journey.

In celebration of International Women’s Day, our film of the month for March MARTHA & NIKI is an inspiration for women and girls, boys and men, and everyone around the world. This film begins by getting our bodies moving with awe-inspiring hip-hop dance and leaves our hearts singing the tune of a complex and beautiful friendship. Swedish director Tora Mkandawire Mårtens spent five years growing and learning alongside Martha and Niki, and the result is a film that pulls back the curtain on two female dance pioneers, revealing a story of strength, hardships, and staying true to yourself.

What is it that draws you to documentary film?

Before I started working as a filmmaker, I was a still photographer for many years. Stills and moving images are very interwoven in my work. Both have the ability to convey things that are hard to describe in words. Pictures speak in silence. What’s great about both stills and moving images is when they manage to create a feeling of their own in the visual language, when the viewer steps into a new world. My goal with the film about Martha and Niki is for the viewer to remember the imagery in the film. I want the feeling in the images to stick with the viewer after they leave the cinema. From square one you should be drawn into the world of Martha and Niki, a visual world dedicated solely to them. A visual language that will symbolize their lives and moods and to bring out their feelings and dreams.

What is your history with documentary film? Is there a red thread that has followed you throughout your career?

Film editing is one of my favorite things in the process of making a film. Anything can happen in the documentary process and I’m often forced to analyze, question and reassess what is important to get across. One of the challenges is preserving my openness throughout the process; that takes great patience and time. I want to have time to try things out, assess difficult choices, edit scenes in different ways, search for the strongest images, create the right mood and tempo in the film overall, try out different kinds of music in different places, and rearrange scenes. Make the entire film play like a piece of music; that is my optimal process. I learned a lot about the documentary process when I made my first feature film Colombianos, particularly in the editing stage.

MARTHA & NIKI is much more than a dance documentary. It is a film about women boldly taking space in the typically male-dominated world of hip-hop dance, friendship, coming of age, ties to our roots, culture, love, and growing apart. What element of Martha & Niki’s story originally drew you to them, and were there any moments while filming that surprised you, inviting you to take a step back and reevaluate where the film was headed?

The first time I saw Martha and Niki dance was on Youtube, I was instantly amazed even felt seduced… no…almost obsessed! Both of them carried so much that needed to get out through dance. I felt so excited about their energy and decided to capture that on film. They’re very different as individuals, which makes their relationship the more interesting to explore. Their friendship really touches the viewer on so many emotional levels. I was instantly swept away by their friendship from scene one. They’re very honest and straightforward about everything and that kind of honesty was exactly what I wanted to portray —nothing was held back, everything is real and upfront—honesty is what moves people. Words and communicating are however an area they’re lacking in. They communicate best through dance and expose themselves entirely. Dancing is really what keeps them connected, it’s also the beauty of their connection. Martha calls it an ‘infatuation’—which comes across in the film and is quite striking to watch. Their love for dance is something they treat with pure honesty and that comes across in each and every move. They go deep and put their hearts into it – the crowd loves it. It’s important to also mention they were pioneers and represented something completely new to the game – beaming of charisma and a confidence that led them to their victory. They crushed all male competitors, which was a first, that was a big deal, it almost came off as a provocation because they were so used to winning. My aim with this film has been to get beneath the surface and present another side of the hip-hop dance world. Hip hop can express so many emotions, there are battles but there’s also a more profound art form that underpins it. Or, as Martha puts it, every time she dances she tells a story, the story of her life. We get to know Martha and Niki in the beginning of the film almost wordlessly via gestures, movements and body language. Only when we see their first defeat does the street dance fade to reveal problems that they experience away from the stage. People said: they’re world champions already, what more is there to say? There’s a tendency towards fixed ideas about how a story should be told, but I think you can do it in many ways. MARTHA & NIKI is also a film about the friendship between two young women from diverse backgrounds. When Martha was 13 she and her family left Uganda for Sweden, and she has never felt at home in the new country. Niki, on the other hand, was adopted as a baby from Ethiopia. And, as she puts it, she’s fed up with growing up with a different skin color and having to put up with all the tired prejudices that go with it. There’s clearly an unspoken sense of being outsiders, mostly for Martha, but for Niki too in a different way. Dance is the means to overcome these feelings. Both of them get such amazing self-confidence from dance, from the coordination of their bodies.

Martha and Niki’s friendship is captivating, and the two of them share a special connection. Martha is a quiet and private person, and Niki works to build trust and communication between them off the dance floor. You manage to capture some very intimate moments between them, yet it also seems like Martha’s walls are never fully torn down. What was your experience building a relationship and trust with the two of them as a director?

We shot this film during a five-year period and I have followed Martha and Niki’s development as human beings and how their relationship changed through the years, so many things evolved during this process. From the start, with the script, I called this film a “love story” (between friends) and I think we captured all the phases that a love story contains. I also call this film a coming of age film, as you can see them grow up and change during the film. Martha and Niki have put a lot of faith in me to make this film, and I wanted to be completely open with them regarding the footage. I think that this increased their faith in me and made them dare to offer more of their inner-selves. By showing them my material, I also avoid having to worry about what they’re going to think of the film when it’s done. One necessary precondition for me as a filmmaker was that they were satisfied and will stand behind the film. Without their faith, there can be no film. The challenge has been to also portray difficulties and conflicts that Martha and Niki face. I always have a great responsibility as a filmmaker to handle the material I collect in a respectful way. I have to say, making documentaries is always a challenge. Getting emotionally involved is part of the role of a director because people open up and share their stories, which I cherish deeply. I’m held responsible for making everyone involved pleased. That includes processing all feelings during the making of the film and dealing with nerves. So, I’m extremely pleased with the fact that Martha and Niki’s participation in the film has played a therapeutic part in their lives, in terms of expressing and dealing with hardships. I appreciate that.

What has been the primary conversation you have observed people are having around the film?

You don’t have to be into dance or hip-hop to watch this film, it moves people regardless.

Many people can relate to the film because we all—or at least most of us—have a close friend with whom our relationship is somewhat complicated. I’ve also noted that people in all ages are touched by the film, from young children to old people. There’s no integral explicit message to it, it rather circles around several messages. But, as a whole, the core message is really about honesty, staying true to yourself, and not to pretend. Our goal was to create an authentic feel to the film, we want to take the viewers with us, to experience the full package by making them feel as if they’re actually there watching the battles live. See the film, if you want to get inspired and enjoy watching people dance—because dance expresses so much without using words. My vision has always been to create an inspiring film that makes you feel that everything is possible. A film that gives hope and makes you happy.

Often after watching documentaries, people feel inspired to apply the lessons learned to their own life. What is this one thing you would recommend to someone after watching MARTHA & NIKI?

We often talk about promoting role models so that young people have someone to look up to and be inspired by. Martha and Niki are definitely role models, but not because they’re world champions. What’s important in the film is not to highlight success and the importance of winning. It is Martha and Niki’s warmth, consideration, humor, thoughts, and how they act towards each other and other people that I think can inspire the audience. It’s their way of being human that makes them role models and inspiring.

MARTHA & NIKI is Influence Film Club’s featured film for March 2017. Each month Influence Film Club hand-picks one of our favorite docs as our club’s featured film to watch and discuss together. Throughout the month, starting with our newsletter and continuing on our website and social media we will extend the conversation by exploring the various issues touched on in the film, providing filmmaker interviews, suggesting ways to influence, and discussing documentaries in general – because after all, We Love Docs.

Interview by: Isis Marina Graham

Alejandro Jodorowsky is a name that brings excitement to the ears of any hardcore film nerd. His psychomagical masterpieces are leave viewers awestruck, and our film of the month reveals to audiences everywhere that one of these masterpieces never saw the light of day – unless of course you consider the tremendous impact its conception has had on the sci-fi genre ever since. Ever seen Alien? How about Star Wars? This documentary will convince you we ought to be tipping our hat, in part, to Jodorowsky for their aesthetics. JODOROWSKY’S DUNE shines a light on the inspiring brilliance, and madness, of one of cinema’s greatest minds and we had the pleasure of interviewing director Frank Pavich discussing his portrait of the greatest movie never made.

What is it that draws you to documentary film? Is there a red thread that has followed you throughout your career?

For me, a documentary film seems a more feasible way to go. I can have an idea or find a story that is compelling, and very quickly, with a small crew, can start working on it almost immediately. The nature of documentary film allows for a more hunt-and-peck method of work as opposed to necessitating a screenplay to be written and roles to be cast, for example. We can explore as we shoot and edit, finding the story as we progress along.

For a pre-scripted film, everything, including the money, needs to be lined up before the first frame is shot. So making a documentary feels like a more realistic way for me to be able to work.

How did you find out about the story of “Dune”? And what ultimately led you to Alejandro Jodorowsky? Is the story of how you met anything as random and fantastical as the many introductions Jodorowsky describes in the film?

It’s a story that has obviously been around for a while, mentioned in books here or there, but it was not terribly well-known. There was a documentary made about Alejandro many years ago called CONSTELLATION JODOROWSKY and that’s where I first saw a glimpse of his famous DUNE book. The DUNE story was only touched on for a few minutes, but it was fascinating.

I’m not sure if there was anything exactly magical about that first meeting – aside from the fact that I was in ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY’S HOUSE! The whole thing was all very Jodorowskian of course. I think he had fun torturing me by placing that huge book on the table between us, but never inviting me to open it. So mean!

As you can tell from what he says in the film, he makes his choices based on his instincts. We can see it in how he chose his Spiritual Warriors. And I think it was the same way between us. To this day he has never asked me what other films I’ve made and he has never asked to see any work of mine. He made his decision purely on that meeting.

Then again, he also now says that he agreed to sit for my interviews because he simply never thought that I would complete the film! So he thought there was no harm in laying himself out there for something that would never see the light of day anyway!

Jodorowsky is an incredible storyteller, and at every turn the story of the pre-production of “Dune” becomes increasingly extraordinary. How much of the story do you think has become mythologized, if any at all?

That’s a good question! It’s funny, but every time I was about to hit my limit of belief, there would be someone else to corroborate his tales. For example, the story he told about meeting Pink Floyd, where he yelled at them for eating their lunch as opposed to speaking with him, was almost too hilarious to have actually happened. But then we spoke with his co-producer, Jean-Paul Gibon, who was there at the meeting, and he could verify that it was in fact all true!

The same goes for the Dali stories. Michel Seydoux verified all of that craziness. And in fact, it’s an even wilder and longer tale. Michel told us about how they had to bring Dali gifts with representations of hippopotamuses for some unknown reason. They also once got stuck in a rowboat, being towed around a lake by Dali’s larger boat, with black smoke spewing into their faces and choking them for the whole ride. Seydoux said that he almost died that day while Dali and his wife sat comfortably in their lounge chairs aboard the larger boat.

So the reality is that there are even weirder tales that we just couldn’t fit in our film.

What has been the primary conversation you have observed people having around the film?

Well, there’s obviously the surface-level story of the never-made film. So naturally, people quite often express their disappointment that his DUNE was thwarted. But what’s really interesting to me is that so many people find the documentary to be inspirational.

I see it all the time on Twitter or on blog postings or even articles here and there. A big conversation is about how after watching the film, people find themselves inspired to go further. And really, what’s better than an outcome like that?

Often after watching documentaries, people want to take action. JODOROWSKY’S DUNE is not a social impact film, but as you say many people walk away from the film inspired. How would you recommend audience members harness the inspiration they feel after watching the film?

That really comes down to the person. Alejandro is an artist, so I assume that many artists may be inspired by his words. But I hope that his thoughts and ideas go further than that. Artist or not, I believe that everyone can take something from his endless supply of positivity. Hopefully the common thread is that viewers walk away feeling that they can do anything, and then they try. That’s the moral to the story, right? It all comes down to Jodo’s final words about DUNE, where he says, “We have to try.”

What would your documentary playlist consist of?

Hmmm, interesting! Well, I always thought that JODOROWSKY’S DUNE would be a great film to screen on the first day of film school.

But everything needs a counterbalance, so taking that into account, I would say that OVERNIGHT (2003) is the great cautionary filmic tale of our time. It’s a story about the ambition but with none of the self-awareness, none of the artistry and none of the humility (or humanity) that Alejandro possesses. It’s truly a remarkable film.

To stick with some of those same themes, I might suggest two of the obvious ones, HEARTS OF DARKNESS (1991) and BURDEN OF DREAMS (1982). These are two wonderful documentaries about two fantastic films that were completed against unimaginable odds.

To take a left turn, I might suggest THE TARGET SHOOTS FIRST (2000). It’s a really great and not terribly well-known film made by a guy who used to work at Columbia House Records in the mid-90s. He would go onto work every day with a video camera and he would just film his day and his coworkers. It’s amazing look at a world that no longer exists.

And maybe I would take a further left turn with HATED: GG ALLIN AND THE MURDER JUNKIES (1994). There is no one like Alejandro Jodorowsky and there was certainly no one like GG, although I do not think that the two of them would get along! This is the first film by Todd Phillips who went on to make R-rated comedies like OLD SCHOOL and THE HANGOVER, which is sort of wild. If you can make it past the opening image, you’ll in for a ride.

Lastly, I would have to list GIMME SHELTER (1970), perhaps my favorite documentary film of all time. There is a slight connection to that film as when I started working on DUNE, I was living in NY, in an apartment previously occupied by the great Charlotte Zwerin, a frequent collaborator with the Maysles and the editor and co-director of GIMME SHELTER. Perhaps her spirit embedded itself into my work?

______

Jodorowsky’s Dune s Influence Film Club’s featured film for December 2016. Each month Influence Film Club hand-picks one of our favorite docs as our club’s featured film to watch and discuss together. Throughout the month, starting with our newsletters and continuing on our website and social media we will extend the conversation by exploring the various issues touched on in the film, providing filmmaker interviews, suggesting ways to influence, and discussing documentaries in general – because after all, We Love Docs.

Interview by Isis Graham

Our film of the month for April is Influence Film Foundation supported MEET THE PATELS and we can’t get enough of this raucous romp through one of life’s rites of passage. Siblings Ravi and Geeta V. Patel introduce us to the tried and tested Indian tradition of arranged marriage, comically situated on American soil. As a first-generation Indian-American, Ravi grapples with the parts of himself that respond to the ways of the old world, while the status quo of his contemporaries also make complete sense, while his sister Geeta captures it all on film. A humorous rollercoaster ride through the amusement park of family relations, the core-shaking questions Ravi confronts resound with anyone out there who has ever contemplated marriage for themselves.

What is it that drew the two of you to make documentary film together?

Ravi: Common problems.

Geeta: As siblings, we avoid making anything together and I still don’t understand how this happened!?

Ravi: It started by accident – just as a home video. And then when we saw the chance to make something personal, something that could make an impact, it became a very exciting prospect. That said, it was very not easy at first because we have such different sensibilities and it took us a long time to learn how to deal with differences. Thanks to this process, I think we are both now better artists, and much closer as siblings.

Both work in film and television, how does your experience of making a documentary compare to your other work? Is there a red thread that has followed you throughout?

Ravi: Documentaries take much longer. I mean it’s tedious and lacking money. That sucks. But it also was film school for me. And making something that matters – I guess you could say it taught me what art is, to me.

Geeta: Documentaries have this magical element of human nature, world events, the complete unexpected and uncontrollable. It’s an experience that is like no other in that the story tells itself to you most of the time, rather than you writing it.

Documentarians often set out to make one film and end up making another – did you have a specific idea about how the film would turn out? And how did that evolve?

Ravi: We initially wanted to make this more journalistic piece, however as time went on, the vérité aspects and the intimacy of revealing our own family and community felt like the stronger film.

Geeta: The most important thing to us was to make a film that our own family would want to watch. As strange as this sounds, it’s a tall order!

How was it for both of you documenting such a personal experience? Did it bring you closer? Was there any point that you felt like you needed to stop filming, or that the film facilitated certain situations? For example, Ravi, do you think without the film as a vehicle, that you would have ever told your parents about Audrey?

Ravi: It’s hard to say what would have happened without this film, however I know that it changed my life and made all my relationships stronger. But yeah, it’s hard, and weird being the subject of your own film. But because I got to see myself from a third party perspective of a director and editor, I think in many ways it did help me try to change, and I guess be a better character in life. Does that make sense?

Geeta: Many times, we wanted to stop making the film. It’s a really uncomfortable and inconvenient process, and may I just add that the camera was really heavy! This film was also a huge test of my relationship with Ravi. At one point, we thought we’d never talk to each other again. This was the point that changed everything because the lesson of the film became the lesson of our relationship: We chose to make our relationship work. We changed for each other. Now, our relationship is stronger, something new, and quite a dream.

I have to ask – what’s going on now? Have either of you found “true love”?

Ravi: Haha.. Everyone asks us that, of course. We want to keep this a mystery.

Geeta: He says that, but it’s all over social media if you google us. Patels love social media.

What has been the primary conversation you have observed people are having around the film? Has it stirred up any unexpected reactions?

Ravi: The film has sparked loads of discussion between parents and their kids.

Geeta: In general, people of all communities and backgrounds have been writing to us about how the film has changed how they deal with their relationships with spouses, friends, brothers, sisters, children… It’s been amazing to hear all these stories!

Ravi: The unexpected stuff: 1) I expected, or at least hoped, that Indians would love this film. I’m still shocked that it seems almost every Indian I know has seen it. That’s crazy. 2) even more unexpected is the diverse audience this film has resonated with. People are relating to it in so many ways I did not see coming.

It’s not often that a documentary can be classified as a romantic comedy, and you manage to do it so well! Many documentaries inspire people to learn more, take action or get involved in some way, and while Meet the Patels might not be your typical doc, is there anything people can do after watching the film?

Ravi: People don’t spend enough time on their relationships these days. We hope they will talk to the people they love and learn how to be in a healthy relationship. It’s really hard! I also think the main thing we are hoping people take from this film is that they just make effort in communicating with the people they love. In many ways, this film is broadly about how to love your family.

Geeta: Yes, as small a step as this sounds, it’s the key to everything in life. This film is indeed a social issue film. It’s just disguised as a funny film. This was entirely our goal and we’re so excited that it’s working.

What would your documentary playlist consist of?

Ravi and Geeta: Hoop Dreams, Ghosts of Cite Soleil, Sherman’s March, Racing Dreams, Roger and Me, Waltz with Bashir

___________________________________________________________

MEET THE PATELS is Influence Film Club’s featured films for April. Each month Influence Film Club hand-picks one (or two) of our favorite docs as our club’s featured film(s) to watch and discuss together. Throughout the month, starting with our newsletter and continuing on our website and social media we will extend the conversation by exploring the various issues touched on in the film(s), providing filmmaker interviews, suggesting ways to influence, and discussing documentaries in general – because after all, We Love Docs.

Interview by: Isis Graham

“Am I a good person? Deep down, do I even really want to be a good person, or do I only want to seem like a good person so that people (including myself) will approve of me? Is there a difference? How do I ever actually know whether I’m bullshitting myself, morally speaking?”

― David Foster Wallace, Consider the Lobster and Other Essays

When is it ok to lie? Is it ever? What about those seemingly harmless little fibs we’ve all passed off as the truth once in blue moon as not to make a bad impression, to avoid insulting someone, or to shield a loved one from unnecessary grief? Are those ok? If so, where does the line begin to blur between good intentions and plain deception?

There could be a whole sub-genre of documentaries devoted to this question. Most of Errol Morris’ oeuvre is devoted to the notion of self-deception and its explication across the ripples of personal and political catastrophe, while countless other filmmakers peel back the falsehoods and fabrications of those looking to leverage their way up social ladders the world over, such as in Alex Gibney’s THE ARMSTRONG LIE, where former biking world golden boy Lance Armstrong’s long denial of using performance enhancing drugs to become the biggest name in the history of the sport is stunningly shattered. Or on a smaller scale, the ruthless door-to-door bible salesman of the Maysles Brothers’ vérité classic SALESMAN exploit low-income families by bending the truth to make that all important extra buck.

Somewhere in between is ART AND CRAFT’s art forger Mark Landis, who duplicates masterworks and donates them to museums for the sheer satisfaction of duping the pros into believing they are authentic. There is certain fear induced adrenaline rush one experiences when attempting to pull the wool over one’s eyes, as there are no guarantees and success only comes with skill. Henry Joost and Ariel Schulman’s CATFISH plays with this notion of thrill seeking through baiting potential lovers via the digital divide. In the age of the internet, one’s identity can be almost wholly invented, while the truth is merely an option to dole out only if completely necessary. Is this entertainment or self preservation?

Some films, such as Vikram Gandhi’s Indian guru hoaxing KUMARÉ, employ deception as a means to greater, altruistic enlightenment. But lying, even with good intentions, is inherently malicious. When the truth finally comes to the fore, feelings will be hurt and trust, no matter how intimate, will be shattered. No films deal with this idea more intimately than Sarah Polley’s STORIES WE TELL, in which the filmmaker’s own mother purposefully obscured her bloodline for the sake of protecting the immediate family unit.

Were these people right in attempting to pass off untruths as gospel? Does this make them a bad people or do their intentions exonerate them? These six films play with the idea of lying and the trick balance between decency and deceitful. Are you a good person?

Kumaré

KUMARÉ is a documentary about a man who impersonates a wise Indian Guru and builds a following in Arizona. At the height of his popularity, the Guru Kumaré must reveal his true identity to his disciples to unveil his greatest teaching of all.

The Armstrong Lie

Sports legend Lance Armstrong’s improbable rise and ultimate fall from grace. Using interview footage from before and after Armstrong’s doping admission, THE ARMSTRONG LIE explores one of the biggest lies in sports history.

Stories We Tell

STORIES WE TELL is a highly original documentary that explores how we construct our own reality through stories. Sarah Polley’s family and friends weave different narratives into a complex portrait of her mother who died when Sarah was eleven.

Art and Craft

Beginning as a cat-and-mouse art caper concerning one of the most prolific art forgers in U.S. history, ART AND CRAFT is rooted in questions of authorship and authenticity, eventually giving way to an intimate story of mental health and the universal need for community, appreciation, and purpose.

Salesman

SALESMAN follows four door-to-door salesmen that walk the line between hype and despair as they ply across the American Northeast and Miami trying to sell expensive Bibles to low-income families.

Catfish

In this tale of electronic attraction, love, deceit and forgiveness, the dark reality of how far one woman was willing to go to soothe her emotional aches and pains is unearthed, and CATFISH asks the question: what exactly can we trust in this age of virtual connections?

After more than a decade of filming in Indonesia, director Joshua Oppenheimer left the country, knowing that he would probably not be able to come back. He brought away the material for two of the most outstanding documentaries of our time, THE ACT OF KILLING and THE LOOK OF SILENCE, our featured films for February. Two films that have the immense power to change the dynamics of a culture by lifting the veil on the daily horrors many Indonesians experience still today because of the 1965 genocide that forever changed their lives. The haunting first film lets the perpetrators speak, leaders of present Indonesian society, eager to reveal their “heroic” acts of killing; in the 2015 companion piece Oppenheimer quietly tells the story about the incredible act of surviving in the face of deeply rooted trauma and bone harrowing terror. Through his work, the survivors have the final say, but now we hand over to the Oscar-nominated filmmaker himself.

What is it that draws you to documentary film?

It is a life practice that allows me to explore the deepest mysteries in human life and perception, and sculpt what I find into an immersive, poetic experience for an audience, a translation of what I discover through the journey of filmmaking.

What is your own history with documentaries? Is there a red thread that has followed you throughout your career?

I think the dominant theme in my work has been pretence and self-deception. By giving people a stage on which they can dramatize their lives, memories, and feelings, I return to the state-of-nature of nonfiction filmmaking: the simple fact that whenever you point a camera at anybody, they start acting out idealized images of themselves, how they want to be seen, how they see themselves. These self-understandings are always informed by fictions, by second-hand, third-rate stories borrowed from the cinema, television, advertising. That is, we make ourselves and our world through fictions. Rather than rush past the self-consciousness that is inevitable when people are filmed, we should work with this self-consciousness, allowing people to make their fantasies about who they are in the world explicit, and creating occasions where people confront those fantasies. In this way, the nonfiction camera becomes a prism that makes visible the myriad fictions that constitute our ‘factual’ reality. I have always been interested in what happens when these fiction scenes are allowed to take over a film’s form. What fever dreams become possible? This is why I tend to refer to my work as nonfiction rather than documentary – I’m trying to avoid the sobriety and journalistic connotations that ‘documentary’ has in the English language.

Rather than pretend to be a fly on the wall, I would rather collaborate with my participants to create occasions that make visible the previously invisible forces responsible for the problems I’m investigating. This is always a transformative moment: in order to function, these forces have depended upon their invisibility. The moment they are made explicit and visible, everything changes – in ways analogous to The Emperor’s New Clothes. People – participants and the audience – can suddenly talk about the forces shaping their lives in ways they could not before.

Many people describe THE ACT OF KILLING as a “game changer” for the documentary genre – why do you think this is? And where do you think the genre is headed?

Building on what I said above, I think the 159-min uncut version of THE ACT OF KILLING – 40 minutes longer than the US theatrical release – is not a documentary at all, but something new, a fever dream, because the fiction scenes created by Anwar Congo and his friends completely take over the film’s form. The uncut “Act of Killing” uses its extra run-time to do a deeper, more profound work – something surreal and dreamlike that viewers may not have experienced before. It is punctuated by moments of absolute silence, pauses that give the viewer space to rest, recover to take in the surreal material – and that makes it feel more real, and consequently more important. The story unfolds more gradually, to a more intimate rhythm, and grows bigger in scope. It offers more time to get close to the characters, to better understand their development. This makes it a gentler, more intimate, and more profound experience.

The uncut version gives viewers time (and extra scenes) to feel Anwar’s evolving doubt, and get lost with him in his nightmares. These begin simply as his bad dreams, but they grow to embody the nightmare of a man living with mass murder on his conscience. They grow further to encompass the nightmare of humanity itself living with genocide and blindness as the foundation of our everyday normality. And as the nightmare grows, Anwar and his friends’ fiction scenes reveal poetic truths deeper than the observational documentary material. The boundaries between fiction and documentary blur. The fiction scenes takes over the film’s form, unmooring it, sending it spiraling into a surreal fever dream. Most significant, though, is the end of the film. In the final act, Anwar’s descent is more complex and honest in the uncut film: his anger and sadism return with a vengeance — and in response to growing regret. Remorse is painful, and the pain makes him angry. He takes it out on his victims, until he finally experiences a shattering, physical recognition of what he has done.

Note that the uncut “Act of Killing” is available in the US on Netflix and DVD as “The Act of Killing – director’s cut”, though this is misleading as director’s cuts are usually made afterwards, and out of regret. The 159-min version is, in fact, the original unabridged film — the full culmination of our eight-year journey making it. It was the main festival and cinema version outside the US, and received the majority of the film’s accolades.

It’s hard to put into words what kind of strange, disturbing feeling it was to watch men who have committed horrible crimes strolling around and describing what they did, often even laughing and smiling. How did you gain their trust and what were your feelings working closely with perpetrators like Anwar?

It took nothing to get them to open up about their crimes. When Adi Rukun, the protagonist of THE LOOK OF SILENCE, asked me to approach the perpetrators back in 2003, I was afraid it would be dangerous. But each perpetrator was immediately open and boastful about the most grisly details of what they’d done. What was harder was getting them to open up about their feelings. Yet once Anwar revealed that he suffered from nightmares as a result of what he’d done, I used this as my opportunity to tell him that I was also haunted by the terrible stories he was telling me. From that point on, I was very open with Anwar about my feelings, though I showed him at every moment that I regard him as a human being. I think this came as a relief to Anwar: he realized that this was a safe space to begin exploring his guilt. Normally, he does not dare acknowledge his feelings of guilt because he isn’t sure how he could continue to live with himself. But with me he saw that he could admit he did wrong (even if only through his body language, his subtext, his description of his dreams), and I would continue to see him as a human being. In a way, Adi Rukun does the same thing: by testing the perpetrators’ eyes, he shows them that he sees them as human, that he’s trying to help them see, and in an intimate way. This helps them open up to him.

I refused to comfort myself by telling myself that these men are monsters, and I am somehow fundamentally different from them, cut from different cloth. And having made this refusal, I bore the responsibility of approaching them as a human being, naked, in a way, entering the darkness of what it must be like for them to live with such horrors on their conscience. And I entered this space refusing to flinch. This was emotionally difficult for me and my crew.

There’s a sequence in the Director’s Cut of THE ACT OF KILLING where Anwar butchers a teddy bear in a film noir scene; it is one of the most important scenes in the movie to me, because Anwar is despairingly embracing the guilt he begins to realize he can never escape. While we were filming it, Anwar stopped the action to tell me that I was crying. I hadn’t realized it. This was the only time I’ve ever cried without knowing I was crying. Anwar asked, “What should we do? Shall we stop?” I said, “We must continue.” In a way I wish I’d stopped, because I went home that night and had terrible nightmares. Indeed, that was the beginning of eight months’ insomnia and nightmares… THE ACT OF KILLING was emotionally frightening to make, while THE LOOK OF SILENCE was emotionally healing. And at the end of it all, I feel I have overcome that most crippling fear of all: the fear of looking.

You said that Adi, the protagonist of THE LOOK OF SILENCE, asked you to approach the perpetrators in THE ACT OF KILLING. Can you explain about the timeline of the two films, how they came to be, and your decision to create two separate works?

I first went to Indonesia in 2001 to help oil palm plantation workers make a film documenting and dramatizing their struggle to organize a union in the aftermath of the US-supported Suharto dictatorship, under which unions were illegal. In the remote plantation villages of North Sumatra, one could hardly perceive that military rule had officially ended three years earlier. The conditions I encountered were deplorable. Women working on the plantation were forced to spray herbicide without protective clothing. The mist would enter their lungs and then their bloodstreams, destroying their liver tissue. The women would fall ill, and many would die in their forties. When they protested their conditions, the Belgian-owned company would hire paramilitary thugs to threaten them, and sometimes physically attack them.

Fear was the biggest obstacle they faced in organizing a union. The Belgian company could get away with poisoning its employees because the workers were afraid. I quickly learned the source of this fear: the plantation workers had a large and active union until 1965, when their parents and grandparents were accused of being “communist sympathizers” (simply for being in the union) and put into concentration camps, where they were exploited as slave labor and ultimately murdered by the army and civilian death squads.

In 2001, the killers not only enjoyed complete impunity, but they and their protégés still dominated all levels of government, from the plantation village to the parliament. Survivors lived in fear that the massacres could happen again at any time. After we completed the film (The Globalisation Tapes, 2002), the survivors asked us to return as quickly as possible to make another film about the source of their fear – that is, a film about what it’s like for survivors to live surrounded by the men who murdered their loved ones, men still in positions of power. We returned almost immediately, in early 2003, and began investigating one 1965 murder that the plantation workers spoke of frequently. The victim’s name was Ramli, and his name was used almost as a synonym for the killings in general.

I came to understand the reason this particular murder was so often discussed: there were witnesses. It was undeniable. Unlike the hundreds of thousands of victims who disappeared at night from concentration camps, Ramli’s death was public. There were witnesses to his final moments, and the killers left his body in the oil palm plantation, less than two miles from his parents’ home. Years later, the family was able to surreptitiously erect a gravestone, though they could only visit the grave in secret.

Survivors and ordinary Indonesians alike would talk about “Ramli,” I think, because his fate was grim evidence of what had happened to all the others, and to the nation as a whole. Ramli was proof that the killings, no matter how taboo, had, in fact, occurred. His death verified for the villagers the horrors that the military regime threatened them into pretending had never occurred, yet threatened to unleash again. To speak of “Ramli” and his murder was to pinch oneself to make sure one is awake, a reminder of the truth, a commemoration of the past, a warning for the future. For survivors and the public on the plantation, remembering “Ramli” was to acknowledge the source of their fear – and thus a necessary first step to overcoming it. And so, when I returned in early 2003, it was inevitable that Ramli’s case would come up often. The plantation workers quickly sought out his family, introducing me to Ramli’s dignified mother, Rohani, his ancient but playful father, Rukun, and his siblings – including the youngest, Adi, an optician, born after the killings.

Rohani thought of Adi as a replacement for Ramli. She had Adi so she could continue to live, and Adi has lived with that burden his whole life. Like children of survivors all across Indonesia, Adi grew up in a family officially designated “politically unclean,” impoverished by decades of extortion by local military officials, and traumatized by the genocide. Because Adi was born after the killings, he was not afraid to speak out, to demand answers. I believe he gravitated to my filmmaking as a way of understanding what his family had been through, a way of expressing and overcoming a terror everybody around him had been too afraid to acknowledge.

I befriended Adi at once and together we began gathering other survivors’ families in the region. They would come together and tell stories, and we would film. For many, it was the first time they had publicly spoken about what happened. On one occasion, a survivor arrived at Ramli’s parents’ home, trembling with fear, terrified that if the police discovered what we were doing, she would be arrested and forced into slave labor. Yet she came because she was determined to testify. Each time a motorcycle or car would pass, we would stop filming, hiding what equipment we could. Subject to decades of economic apartheid, survivors rarely could afford more than a bicycle, so the sound of a motor meant an outsider was passing. The Army, which is stationed in every village in Indonesia, quickly found out what we were doing and threatened the survivors, including Adi’s siblings, not to participate in the film. The survivors urged me, “Before you give up and go home, try to film the perpetrators. They may tell you how they killed our relatives.” I did not know if it was safe to approach the killers, but when I did I found all of them to be boastful, immediately recounting the grisly details of the killings, often with smiles on their faces, in front of their families, even their small grandchildren. The contrast between survivors being forced into silence and perpetrators boastfully recounting stories far more incriminating than anything the survivors could have told made me feel as though I’d wandered into Germany 40 years after the Holocaust, only to find the Nazis still in power.

When I showed these testimonials to those survivors who wanted to see it, including Adi and Ramli’s other siblings, everybody said, more or less: “You are on to something terribly important. Keep filming the perpetrators, because anybody who sees this will be forced to acknowledge the rotten heart of the regime the killers have built.” From that point on, I felt entrusted by the survivors and human rights community to accomplish work that they could not safely do themselves: film the perpetrators. All of them would enthusiastically invite me to the places they killed, and launch into spontaneous demonstrations of how they killed. They would complain afterwards that they had not thought to bring along a machete to use as a prop, or a friend to play a victim. One day, early in this process, I met the leader of the death squad on the plantation where we had filmed The Globalisation Tapes. He and a fellow executioner invited me to a clearing on the banks of Snake River, a spot where he had helped murder 10,500 people. Suddenly, I realised he was telling me how he had killed Ramli. I had stumbled across one of Ramli’s killers. I told Adi about this encounter, and he and other family members asked to see the footage. That was how they learned the details of Ramli’s death.